An Entrepreneurial Start

By all accounts, David Craig was something of an entrepreneur, but in those days - the 1920s and 1930s - people called him a 'company promoter'. Craig's preferred strategy was to help introduce overseas brands to Australia; for this he received a fee for setting up the company and then sold out, preferring not to have any long-term involvement with the enterprise. He is reputed to have bought the Australian rights to Life Savers sweets and Smiths Potato Crisps. In the 1930s, Craig and his associates secured local patent rights from the United States for an industrial process to manufacture fibreboard from woodchips. He resigned his directorship after the company had built a plant at Raymond Terrace, before defence orders during World War II helped it into profit.

In 1939 Craig led a consortium seeking approval to manufacture bitumen from imported crude oil in Sydney. The application was rejected in 1940 by the Advisory Committee on Capital Issues. Craig appealed to Arthur Fadden (later Sir Arthur Fadden), the Federal Treasurer and, after a Tariff Board inquiry the appeal was again rejected. However, Craig persisted and finally, after seven years, the official prospectus was released to the public on 19 February 1946. Boral was born. Bitumen and Oil Refineries (Australia) Limited was incorporated on 4 March 1946 under Craig's chairmanship, with part-owners California Texas Oil Company Limited (Caltex) supplying the crude product from overseas. Land was purchased at Matraville on Botany Bay, New South Wales, and the first Australian-owned bitumen and oil refinery was officially opened just over a year later in March 1947. The ceremonial laying of the foundation stone went ahead despite the fact that the refinery was only half completed and Randwick Council had reluctantly taken Bitumen and Oil Refineries to court over the construction of a refinery so close to residential areas.

Jim Cornell was the first employee of the company, initially working out of David Craig's office at 24 Bond Street near the present Sydney Stock Exchange. He remembers being sent out to look at the proposed refinery site at Matraville and not being able to locate it in the desolate sandhills on the road to La Perouse. Cornell's expertise was in customs and shipping, and he was employed by Bitumen and Oil Refineries to instruct Caltex's New York office on the correct packaging and marking of the new plant equipment for Australian Customs. The acronym 'Boral' was first used as the company's shipping mark.

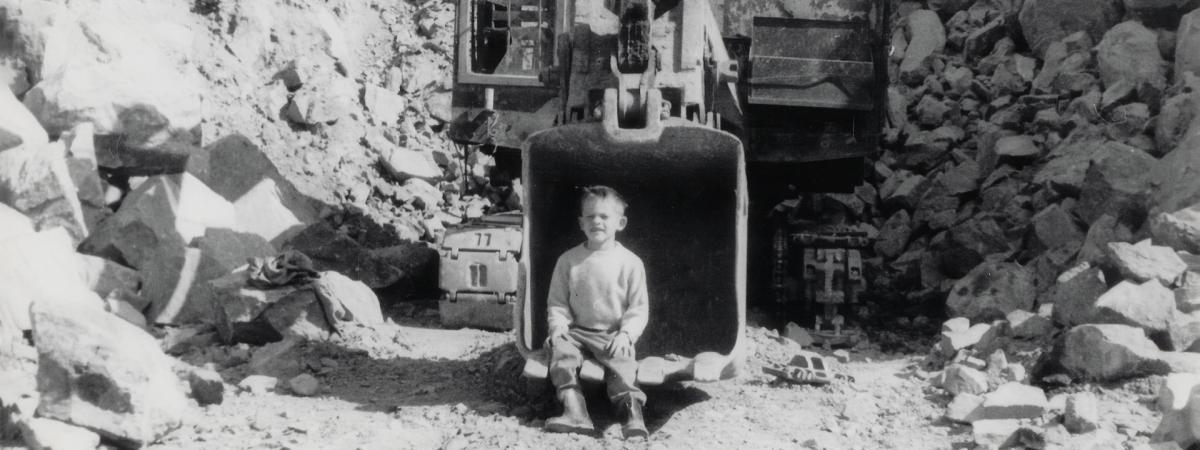

Building the Refinery

The first year of operation was difficult. Establishing the refinery took longer than anticipated, due to the shortage of building materials and skilled labour. The refinery construction office at Matraville consisted of old army huts and trestle tables; the typewriters regularly jammed because of the sand.

The company had great difficulty in obtaining steel to build the refinery because of the scarcity of materials. However, the British Naval Store yards, which had a plentiful supply, were nearby. The steel they had stockpiled during the war years to repair military ships and submarines was no longer of use to them. Bitumen and Oil Refineries bought these steel reserves but the refinery needed to re-roll the steel for use as storage tanks.

You Can't Beat a Navy Man

Once construction work started on the refinery, the first operational employees were recruited. They were sent to the United States for six months training with Caltex. About half of the new employees were ex-navy personnel. When they returned, the refinery had not been completed and they provided additional manpower to speed up the construction work.

Once the refinery was operational the ex-navy men were seen to be cleaner in their habits than their non-navy colleagues. According to Jim Cornell, 'They'd all had war experience and were used to keeping everything "shipshape" - if they dropped a bit of oil it had to be cleaned up. Wherever the navy people worked at the refinery the area was always kept spotless. If anything needed polishing, they polished it.'

Even after the war was over, young men could volunteer for a six- or twelve-year commission with the navy. When they were discharged and came ashore at Garden Island in Sydney, Bitumen and Oil Refineries would offer them employment, even if the company didn't have a permanent placement for them at the time. Eventually most of the plant workers at the refinery were ex-navy men.

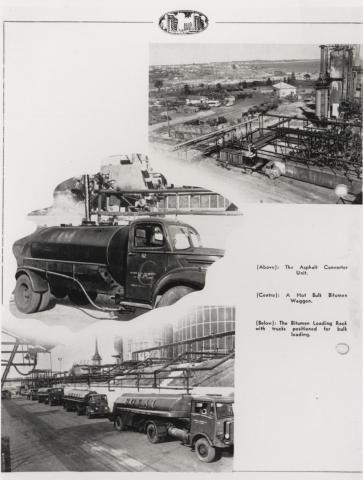

The First Delivery Fleet

Bitumen and Oil Refineries' first fleet of delivery trucks consisted of ex-army water tankers converted to carry bitumen. The Australian and United States military forces were disposing of trucks and vehicles after the war, and held a big auction in Darwin. The water trucks were auctioned in job lots of ten - three or four were new, another three or four second-hand and three were 'bombs'. At the auction, Bitumen and Oil Refineries bought three lots of trucks and sent a team of men to Darwin to drive them back to Sydney. Not surprisingly, seven or eight failed to arrive because the trucks were in such bad condition; the drivers were forced to abandon them where they stopped on the side of the road. For bulk haulage the company bought about four hundred 'Bailey bridge pontoons'. Jim Cornell recalls, 'These were seven-foot by five-foot tanks used during the war. They could be linked together and the army would run them across rivers. We bought them, cut holes in the side, mounted them on trucks and used them as [bitumen] delivery tanks for about ten years.'

The Caltex Connection

Under the legal agreement negotiated with Craig, Caltex had a 40 per cent shareholding but its financial contribution was satisfied by supplying Bitumen and Oil Refineries (Australia) Limited with crude oil. Bitumen was manufactured from very heavy residual oil. For ease of transport, this oil was mixed with petrol to make it fluid enough to be handled by tanker to Sydney. It was then fed into 44-gallon drums for bulk sale on the local market. The plan was for Caltex to come to Australia and assist in building a small refining unit - not a full refinery by any means, but basically a 'fractionating tower' that would separate the petrol from the heavy residual oil. Caltex would then take back the petrol and market it on its own account, and Bitumen and Oil Refineries (Australia) Limited would use the heavy residual oil to manufacture and market bitumen.

Getting Organised

At the time Bitumen and Oil Refineries (Australia) Limited was incorporated, no chief executive was appointed. There were seven men on the original Board, four Australians and three Caltex nominees consisting of one American and two Australians. The business was managed by the accountancy practice P.L. de Monchaux, Willcock and Griffin. Elton Griffin (later Sir Elton Griffin) was one of the subscribers to the Formation Agreement as well as the founding financial director.

David Craig severed his connection with the company because of ill-health in 1947, and died in 1950. Gerry Wells, who became involved with Bitumen and Oil Refineries in those early days and later became deputy chairman, recalls: 'I'm left with the idea that Craig dipped out on his set-up fee because it turned out that he was not party to the Formation Agreement that established the company. In those days you couldn't take a benefit under a contract unless you were a party to that document.' He did, however, negotiate a royalty with Caltex that helped finance his family for the next twenty years or so.

The Official Opening

The laying of the refinery's foundation stone took place on Friday 28 March 1947. William McKell, Premier of New South Wales at the time, agreed to perform the ceremony. The engraving had been organised some months before and the stone was stored in the company warehouse until opening day. About four days before the scheduled ceremony, word arrived that McKell was likely to become Governor-general of Australia. Two days later he was made Governor-general-elect, to be sworn in on the following Monday. James McGirr was appointed state Premier-elect.

The problem was whether McKell, shortly to be governor-general, could lay the stone as Premier. Company executives quickly checked the correct protocol with various government departments. Negative responses from all quarters suggested that the only solution was to invite McGirr as New South Wales Premier-elect to perform the ceremony.

Several stonemasons worked through the night to prepare the new stone. A makeshift wall had been constructed specifically for the ceremony and McGirr unveiled it within hours of its completion. The management had not yet decided on the site of the administration office and, after the celebration, the wall holding the foundation stone was promptly dismantled and the stone returned to the warehouse. During the flurry, Elton Griffin's name was misspelt, a fact which was not noticed until a year or two later when the refinery was completed and there was no chance of having the error corrected.

By 1947 it became clear that Bitumen and Oil Refineries needed a full-time manager and Elton Griffin was offered the position. The refinery produced its first run of crude oil in July 1948 and by April of the following year was manufacturing bitumen and heavy oils. The production of solvents and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) did not begin until later.