Boral Makes Some Smart Moves

Marketing of the Matraville refinery products was always a major concern for management. In the early 1960s, Bitumen and Oil Refineries found itself with a surplus of oil that it needed to offload. The company liaised with the engineering department of New South Wales Railways, helping them convert their coal-burning locomotives to the use of oil. This venture was successful and the company contracted to supply oil to them.

The company also expanded in related businesses. Until 1963 Bitumen and Oil Refineries made no significant takeovers, except in road-surfacing operations. Its subsidiary, W. B. Carr Constructions, had asphalt-spraying operations in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia. However, Bitumen and Oil Refineries essentially marketed bitumen and fuel oil in New South Wales. Most of the white products - the petrol and kerosene and distillates - were taken back and marketed by Caltex. Griffin saw an expansion opportunity in the spraying of bitumen and the mixing and laying of asphalt, and bought BHP's road-surfacing operations in New South Wales. They also acquired one or two similar smaller operations in Victoria such as Dammann Asphalt.

Eric Neal (later Sir Eric Neal, and Governor of South Australia), who succeeded Griffin as managing director in 1973, recalls, 'In those early years Griffin was the operator and [Sir] Ian Potter of Potter and Partners, a Melbourne stockbroking firm, was a de facto corporate planner (Potter was on the Boral Board for many years). They made some very fine acquisitions which were of great benefit to Boral but there wasn't any particular pattern to them, they were very diverse. The company's strategy was somewhat opportunistic and Potter played a key role in this - he was in his heyday in the 1960s.'

Potter advised Griffin on the acquisition of asset-rich companies such as Huddart Parker and Mount Lyell by Bitumen and Oil Refineries. Those early takeovers were 'add-ons' to the company as a limited oil refiner and marketer of petroleum products. Even the investment in Huddart Parker Industries, a leading Australian coastal shipping group, had practical applications. Apart from greatly increasing the financial strength of the company, this purchase gave it access to additional outlets for its oil products using Huddart Parker's well established shipping routes. The acquisition cost Bitumen and Oil Refineries nearly 2 million pounds, whereas Huddart Parker's net asset value amounted to more than 6 million pounds.

The Nickname Becomes Official

At the Annual General Meeting in October 1963, the shareholders unanimously agreed to officially change the name of the company to Boral Limited. By that time the acronym was widely used both within the industry and by the press of the day. The Board stated: 'Since the company was incorporated in 1946 it has been referred to as "Boral" and this name is now widely used in the industry, by customers and in financial journals. The directors therefore consider it would be appropriate that the name of the company be changed to Boral Limited - by special resolution at the Annual General Meeting.' So in the good Australian tradition, the nickname became official.

At that same meeting, the directors altered the Articles of Association of the company to increase the board of directors from seven to nine members. This was considered appropriate in view of the expansion in Boral's activities. Caltex retained the right to nominate three board members.

The Gas Supply Company

One of the first major strategic moves for Boral came with the acquisition in 1963 of the Gas Supply Company. This group consisted of twenty-eight coal gas companies ranging from Cairns in the north, down the east coast as far south as Portland in Victoria, and as far west as Broken Hill. The takeover of the Gas Supply Company came as a complete surprise to that company's employees and management. There were no prior negotiations with Gas Supply - according to one version of events, Boral's financial controller at the time, Malcolm Irving, delivered the news personally; another version has Hugh Craig presenting general manager Jack Mackenzie with the daily paper featuring the takeover as its lead financial story. Boral's ready victory was at least partly due to the inclusion in its offer of 43 shillings cash for each share, significantly more than the market price at the time.

At the time the Gas Supply Company Board and management had recognised that the coal gas industry had a limited future. As with the United States and Europe, the trend in Australia was towards the use of oil refinery products for making gas either by catalytic reforming or by distributing liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). Significantly, the Gas Supply Company had moved in 1962-63 to replace its coal gas operations with LPG.

Gas Supply had recognised that LPG would be the fuel of the future for country gasworks. Amoco had announced its intention of building a new refinery in Queensland. Most of the other major refineries had signed up to offload their LPG supplies with other gas companies; Caltex to the Australian Gas Light Company in Sydney, Shell at Geelong and Mobil at Altona had relationships with the Gas and Fuel Corporation in Victoria. Gas Supply recognised that if it could come to an agreement with Amoco it could market LPG in Queensland, its largest state of operations. A contract was being negotiated between Gas Supply and Amoco when Boral made its takeover bid for the Gas Supply Company. Eric Neal had just been appointed assistant chief general manager of the Gas Supply Company, a promotion from manager of the Ballarat Gas Company. Neal said of the negotiations, 'I am convinced that this move [to obtain Amoco's LPG] by The Gas Supply Company was unknown to Griffin'. The contract with Amoco went ahead after the takeover.

Meanwhile, Boral had acquired, through the takeover of Huddart Parker, a half interest in Hebburn Collieries and Elrington Colliery in New South Wales, owned with BHP. Neal commented, 'Griffin was ever an opportunist, a very brilliant man. He quickly recognised that in the interim period - while Gas Supply was moving away from coal gas - coal could be supplied by these two collieries; but ultimately LPG, which was a by-product from the Boral refinery in Sydney, could be marketed in New South Wales through the gas companies at Broken Hill, Goulburn and Albury. Queensland, with the Amoco refinery, provided an opportunity for Boral to negotiate a contract to take the whole bitumen output, as well as the LPG, from the Amoco refinery.'

So while the original motives for taking over the Gas Supply Company were somewhat blurred, in the months that followed Boral saw an even greater opportunity to market LPG, both from its own refinery in New South Wales and from the Amoco refinery in Queensland.

The Gas Supply Company History

In 1886, John Coates and Company was formed to construct gasworks and other engineering projects around Australia. It erected forty-seven gasworks throughout Australia. Many were built under contract to local councils, while others were erected for private companies formed by enterprising citizens.

By the mid-1920s many of these independent gasworks were experiencing difficulties because of their limited scope of operations. Electricity had taken over from gas as the preferred energy source for lighting. These independent utilities had no resources to tackle the competition from electricity, as gas had not firmly established itself as the best fuel for cooking and heating by this time.

To try to combat this growing threat from electricity, the Gas Supply Company was incorporated on 29 December 1926. Agreements were entered into by which the new company acquired all the gasworks of the old independent gas companies - they then became branches of the new entity. Over the ensuing years the company acquired many more country gasworks throughout the eastern states. Many of these, perceiving the benefits to be gained from being a part of a large company, approached the Gas Supply Company to purchase them.

Bottled LPG became available in Australia in 1957. The Gas Supply Company, in conjunction with the Gas and Fuel Corporation of Victoria and the Geelong Gas Company, first marketed the product in Victoria and adjacent border areas. This market soon expanded to include New South Wales, Queensland and later Papua New Guinea.

Once Boral acquired Gas Supply in 1964, bulk LPG gas terminals were installed in many New South Wales and Queensland country towns. Some regional areas had already seen the closure of their traditional gasworks in favour of LPG distribution by means of refillable in situ cylinders on the gas consumer's property.

Around the time of the Gas Supply Company takeover and until the end of the 1960s, a number of significant takeovers took Boral into quarrying. A natural extension of this move was into the pre-mixed concrete industry.

Albion Road

In January 1965, Boral expanded its quarrying interests with the acquisitions of Albion Quarries and Reid Quarries, the two largest Melbourne-based quarry operators. The quarry business provided Boral with the other major material needed to combine with bitumen in hot-mix asphalt and road paving. The Melbourne operations were combined to form Albion Reid Pty Ltd.

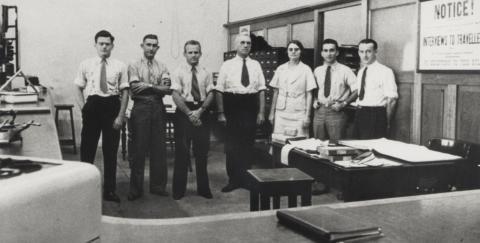

Boral Introduces Computers

The cover of the 1965 Boral Annual Report featured a magnified picture of the memory of the IBM System/360 computer. Tom Murray, then Boral's chairman, said in his message to shareholders, 'In line with the rapid growth of the company it became necessary to consider the best and most modern method of handling the increasing volume of information generated from ail sources, and the Board decided to install an IBM System/360 computer. Plans are already well advanced and the essential staff are undergoing the necessary training.' Griffin was not very enthusiastic about this innovation, and Boral did not become fully computerised until well after he had retired.

Boral Reaches Twenty

In 1966 Boral celebrated its twentieth anniversary, with minimal fanfare. The Boral Group had 2967 employees and more than 33,000 shareholders and the total group revenue reached $75,901,000 - a 4.6 per cent increase on the previous year. In 1967 John O'Neill took over from Tom Murray as chairman of Boral Limited. O'Neill was a senior partner with Murphy and Moloney, Boral's solicitors, when he was invited to become a director in April 1967. Later that year he was appointed chairman of the board.

Boral in 1966 | |

| Total Sales Revenue | $75,901,000 |

| Net Profit before tax and depreciation | $10,512,775 |

| Net Profit after tax and depreciation | $3,681,759 |

| Assets | $99,275,016 |

| Number of Shareholders | $33,203 |

| Dividends paid | $3,113,944 |

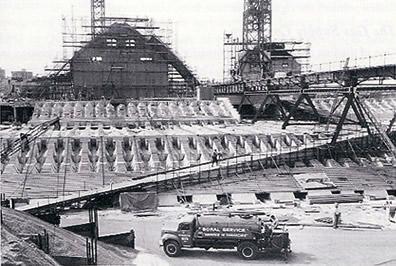

In the late 1960s the Matraville refinery was also being upgraded. A new Isomax unit was installed at a cost of 2.5 million dollars to produce high-octane gasoline previously unavailable in Australia. The refinery was shut down for the month of February 1968 because of a strike by Australian Workers' Union members. Work resumed on the last day of the month following a settlement between the company and the union on the terms of a new industrial agreement for refinery operators. This was the first prolonged strike in Boral's history. In July 1968, Boral employees who were members of the Transport Workers' Union were also involved in an Australia-wide industrial dispute.

Crude Oil Discovered in Australia

Until the late 1960s Boral's strategy was a combination of long-term perception and opportunism. But with the discovery of crude oil in Australia in 1968-69, this strategy had to change significantly.

When crude oil was found in Australia another problem arose between Boral and Caltex. The original arrangement with Caltex had been that Caltex supplied the feedstock to Boral and took back the refinery products that Boral didn't market. Boral kept the specialised products - the bitumen, heavy oil, some solvents and LPG; Caltex took back the petrol, kerosene and distillates.

All Australian refiners had to take a share of Australian crude oil production in proportion to their retail sales. Because Caltex's sales were enhanced by the add-on or buy back of Boral's refined products, the company now found itself with quite a significant allocation of Australian crude oil that it had to take and refine. Instead of being solely an importer from its own crude oil wells elsewhere in the world, Caltex was obliged to take an allocation of Australian crude oil based on its total sales. Boral had a much smaller allocation because its retail sales were not substantial, but it still had to dispose of the white products. Caltex was not happy about having to sell on Boral's behalf products not made from their own crude oil supply.

Total-Boral Limited - A Marriage of Convenience

Total Holdings, a wholly owned Australian subsidiary of the major French company Compagnie Francaise des Petroles, was in the reverse situation to Boral. It had a modest marketing operation retailing petrol in Australia, but nowhere to refine its allocation of Australian crude oil. The joint venture between Boral and Total in 1968-69 was a marriage of convenience. Boral placed its refinery interests into a new oil refining and marketing company called Total-Boral Limited and ceased to have an active role in the management of the Matraville refinery, other than through representation on the board. Peter Finley (later Sir Peter Finley), who was appointed to the Boral board in 1969 and later became Chairman, recalled, 'I don't think that either the French or Griffin found the other party an easy bedfellow - eventually Griffin decided Boral would withdraw from the oil industry altogether'.

A Foot in Both Camps

Before Griffin made the decision to leave the oil refining industry, he was still looking for local marketing opportunities. Bass Strait crude oil was particularly suited to aeroplane or jet fuel, and Griffin was determined to find an outlet for these new, specialised products. They were not easy to place but, while flying to Melbourne one morning, he suddenly decided that Boral should buy shares in Ansett and take a position on that company's board. He made his strategic move in the hope of influencing fuel contracts. Boral duly bought a significant stake in Ansett and Griffin took a place on the board. The original intention of selling fuel to Ansett was never carried out, though the shareholding was eventually sold at a handsome profit.

The Turning Point - Going for Gas

The Gas Supply Company had undergone considerable reorganisation since its purchase in 1963. In 1968 Boral was developing gas business opportunities in New Guinea and Eric Neal was managing the Queensland gas operations. Neal saw that if Boral bought a shipping tanker the company could expand the gas business and he sent a proposal to Boral headquarters in Sydney that Boral should buy a small shipping tanker to haul LPG from Brisbane to Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands. This would be quite a venture in itself but Neal also suggested that Boral should obtain a five-year contract to do this from the Australian government, which administered Papua New Guinea at the time. The proposal proved a turning point in Neal's career.

He heard nothing for some weeks until Griffin came to Brisbane, walked into his office, sat down and asked, 'What's all this nonsense about buying a tanker?'.

Neal recalls, 'At that point I could sense he wasn't in favour of it, so I could have backed off, but I simply said quietly, "Well Mr Griffin, if that's your view it would appear you haven't read the report I sent down to you in Sydney".' Griffin responded by asking, 'What report?' Neal found a copy which Griffin sat and read. Pointing at the bottom line, he asked, 'Well what about this? Where does this figure come from?'

After about fifteen minutes of going through all the figures, Griffin said, 'This is a good idea, but it's all dependent upon you winning that five-year contract to supply Papua New Guinea. If you do, you've got your ship.' With that, he went back to Sydney. About two months later Neal sent him a telex: 'Five-year contract awarded by Department of Supply today'. Griffin rang him immediately and said, 'Well, you'd better head off to Japan and find a tanker!' About a year later, Griffin came back to Brisbane and invited Neal and his wife to spend the weekend at the Gold Coast with him and his wife. At that stage there was a lot of talk about natural gas coming to Sydney. Griffin said, `We don't need to worry about it at all, the LPG from our Botany refinery will compete with natural gas, we won't have to change our strategy at all.'

When Neal told him that he wouldn't make any money out of this strategy, Griffin replied, 'Rubbish!' (which Neal remembers seemed to be one of his favourite words), and repeated 'We can compete with natural gas with our refinery LPG, we don't need to worry about it.'

Neal then said, 'There is no question Boral can compete, but the price at which we will have to compete means that we won't make any money out of it'. A heated argument ensued in which Griffin told Neal he was wrong and out of touch with industry developments. Dinner resumed on a quieter note.

A couple of months later, Griffin asked Neal to come to Sydney. Neal recalls, `He was always one to check things out, and he said to me at that meeting, "I want you to run the whole of the Boral Gas Group". It appeared he may have done some independent research to check the competitive situation of natural gas and LPG in bulk, realised he was wrong, and that a change of strategy was needed.'

Boral Bails Out of Refining

Unlike the large multinational oil companies, Boral didn't have access to materials or oil leases throughout the world. Griffin came to realise that the company should get out of the oil industry altogether. Boral disengaged from the oil industry but had to decide where to direct its energies. After the sale of the 50 per cent refinery interest to Total in 1968-69, Boral decided to embark on a strategy of acquisition in the building materials and products area. They already had Boral Gas - or Gas Supply as it was then called - the Albion Reid quarries and road-surfacing operations in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia.

Laying the Foundations for the Future

In 1968-69, Boral acquired 60 per cent of Warringah Brick and Pipe Works in Sydney (which ceased operations two years later) and bought Brittain Bricks and Pipes Limited in Queensland outright. Glen Iris Brickworks in Victoria was bought in 1970. These acquisitions, with the more modest takeovers of Besser and Jayblox, both of which produced concrete products in New South Wales and Queensland, established Boral more firmly in the building materials industry.

Brittain Bricks History

Brittain Bricks was founded in 1887 by William Brittain who had arrived from England in 1883. Brittain had learned the art of brick-making in Warwickshire. At the age of eighteen he had been given the responsibility of 'burning bricks', or firing bricks using wood as fuel.

After he arrived in Brisbane, Brittain found work at Petrie's Albion brickyard again 'burning bricks'; by this time the industry had moved to using coal-fuelled kilns. He later worked for Waterstown and the New Chum brickworks at Ipswich, Queensland where he took charge of the manufacturing section and the construction of a new plant.

After four years Brittain went into business for himself. He rented some land at Dinmore near Ipswich on the Brisbane Road and started manufacturing hand-pressed bricks. The demand for these bricks diminished with the introduction of machine presses to Australia in the early 1900s which mechanically cut the bricks.

Brittain could not afford to import a machine pressing plant, so he set about making his own using timber grown on the property. This proved successful and his bricks were considered equal to other locally made products. Output increased, and Brittain bought a 'state-of-the-art' Bradley and Craven machine brick press.

After nearly twenty years at Dinmore, the clay supply ran out and Brittain bought another property at Darra, where Boral's brickworks remain. The business was expanding; soon another plant was installed to manufacture clay pipes. The business made steady progress and in 1915 was incorporated as a proprietary company, though Brittain Bricks did not become a public company until 1968.

At the Darra brickworks, the burning process was initially carried out by wood-fired intermittent kilns that, over time, were converted to coal. The brick industry generally moved to continuous gas-fired Hoffman kilns and finally to the modern Tunnel kilns, which are fired by natural gas. Brick production at Darra initially used dry press machines, eventually superseded by the modern wet-extrusion methods in the early 1950s; both methods are still used at the plant. The wet-extrusion process, used to manufacture wire-cut bricks, involves ascertaining the water content of the clay and adding water if necessary so that it has the right consistency. This mixture is then forced through a machine that pushes the clay out in a long rectangular column, which is then wire-cut into bricks, much like a bakery bread slicer. The bricks are then dried in tunnel dryers before being fired in the Hoffman kilns.

When Boral took it over in 1969, Brittain was in the middle of an expansion campaign. This campaign intensified under Boral direction. Four kilns were added between 1972 and 1981, taking the plant's total brick capacity to 120 million bricks per year.

In 1970 the production of clay pipes was boosted with the installation of a specialty Bickley kiln and new manufacturing plant to replace the old `hand-production' method. This continued to operate for a number of years, despite the introduction of PVC piping which eventually took over the market. In 1981 the clay pipe plant was finally closed.

The Boral Book, 1969

By 1969 Boral's business had grown and diversified to such an extent that management felt that the staff needed to be better educated about the Group's activities. To facilitate this an independent company was contracted to produce a staff magazine, The Boral Book. The second edition of this staff magazine opened with the following:

- Q. Which organisation do you know that's just as much at home making bricks as it is refining petrol, laying runways, producing concrete, operating container shipping piping gas, working quarries, among other things?

- A. Your organisation! That's the simple answer - the company you work for. Because your company is one of the many in the Boral Group, and that means you've got a stake in something big. We think you're as big as any part of the Group, because you're the people who make it all possible. There's more about you and us inside. Come on in.

The Boral Book contained various articles on companies that were part of the Boral Group and staff profiles, including a piece on Queensland Oil Refineries' bitumen depot at Bundaberg:

- Admittedly it's got the advantage of being sited where it is. That stretch of the Burnett River is part of the King's Cup course rowed over recently in the regatta up that way, and the tropical greenery helps soften the lines of the installation a good deal. But it's still a bitumen depot, and the real reason why it looks so good, why its all silver and clean black and immaculate white is Ted Stopford, the manager.

- There seems to be something about service in the Navy which stamps itself on a man, and when the man's had thirteen years in the service and come out of it a chief petty officer, the marks are unmistakable. They include a liking for orderliness, a capacity for getting on with people and a strong desire to be doing something useful.

On 1 March 1969 Tom Murray died while still in office as a director. He had been chairman of Boral for twenty years, until 1967. The obituary in the 1969 annual report said of Murray, 'His period as chairman covered an era of tremendous growth, during which his guidance and advice proved invaluable'.

In March 1969, Boral's construction materials division greeted with enthusiasm the Commonwealth--States Roads Agreement, a Federal government initiative to improve Australia's roads. Prime Minister John Gorton's official statement said in part: 'The Commonwealth government proposes to provide $1252 million over the next five years toward the cost of roads in the States. An increase of over half a billon dollars or 67 per cent is, we think, a very generous one and one that must considerably improve the standards of roads in this country over these five years.'