The First Changing of the Guard

By the time Griffin promoted Neal to general manager of the Boral Gas Group in 1970, Boral had acquired brickworks, quarry and concrete operations in Melbourne and brickworks and concrete product operations in Sydney and Brisbane. It had also just acquired a company called Steel Mills Limited in Sydney which had a small Queensland branch. Boral was firmly entrenched in the building materials business - the path was set.

In February 1970 a new company, Boral Basic Industries Limited, was formed to take over the activities of all the group's companies operating in quarrying, sand, pre-mixed concrete and in bituminous road surfacing and bituminous products in all states. Fifteen per cent of the capital was offered to Boral shareholders.

The Gas Supply Company was operating in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria. In Victoria, it managed eight or nine country gasworks, Ballarat being the largest branch. Increasingly Boral Gas found itself in competition with the Victorian Gas and Fuel Corporation (VGFC). The VGFC had a policy of low prices and, being a government organisation, it did not have to make a profit. The price that Gas Supply had to charge its customers to earn an income on its Victorian investments (after tax) was prohibitive.

Finally George Todner, an associate director of Boral, was given the task of negotiating the sale of the Victorian operations to VGFC. Late in 1970 Gas Supply sold right out of Victorian town gas and LPG operations. As part of the deal it also entered into an agreement with the state government utility that it would not compete in the gas market in Victoria for the next ten years.

Boral's Gas Division was left with $3.5 million. This money, because it had been originally borrowed under a semi-government trust deed, could only be reinvested in gas utility operations.

Neal pointed out to the Boral board - which at that stage was chaired by John O'Neill with Elton Griffin as managing director - that there was no way Boral Gas could invest that amount of money in LPG operations; there just wasn't the scope for it at that time. Neal suggested that the more sensible course would be to take over the Brisbane Gas Company, which would give Boral's Gas Division an even stronger base in Queensland, where it already had its major gas business.

The Brisbane Gas Company

In 1971, Neal was given the job of handling the acquisition of the Brisbane Gas Company. John Rowell (later Sir John Rowell) was a partner in the legal firm, Neil O'Sullivan and Rowell, the Queensland associates of Murphy and Moloney, Boral's New South Wales solicitors. (Rowell became a director of Boral in 1974.) This firm had acted for Boral on a number of occasions, including the incorporation of Queensland Refineries in 1954. Rowell was instructed to approach the larger Brisbane Gas Company shareholders to try and acquire a position in the company so that Boral could then make a full takeover bid. Rowell remembers, 'I was stumping up and down Queen Street in Brisbane trying to acquire shares. This was not very successful. The Queensland business community was a very insular place at the time and didn't take kindly to the idea of a southerner moving in on their turf.'

Rowell regularly reported progress to Sydney; after a couple of weeks it became clear that the share acquisition strategy was unsuccessful. Neal said, `I can well remember the stage when all appeared lost. Boral's offer had been totally rejected by the board of the Brisbane Gas Company and Boral's local directors weren't terribly enamoured of the whole proposal either because they were part of the Brisbane establishment and were somewhat embarrassed that we were involved in a contested takeover.'

Neal had been reading a book about acquisitions and realised that this stalemate could be resolved by approaching the shareholders directly with a `first come, first served' bid. No one at Boral or Neil O'Sullivan and Rowell had come across this method of acquiring shares in companies before. It involved a representative for Boral getting up on the Stock Exchange floor and offering to buy a parcel of shares (for example 20 per cent, at a specified price) in the desired company. Once the required percentage of shares had been obtained the offer closed, hence the description 'first come, first served'. Neal rang Griffin at home on the weekend and canvassed the idea of using this approach with him. Griffin said, 'Go to it'.

To represent Boral on the Queensland Stock Exchange floor Griffin enlisted Frank Charlton who was on the Queensland board of the City Mutual Life Assurance Society Limited. As this had never been done before, and knowing the local opposition to Boral's advance, Charlton was reluctant, not at all confident the offer would work. Griffin told Charlton that if he wouldn't do the job, Griffin would find someone else who would and Charlton finally agreed.

However, nobody had let Rowell know that Boral was trying this innovative approach to the takeover. He was still visiting potential Brisbane Gas Company sellers with a $3.40 buying price, not realising that Charlton was offering shareholders $3.50 on the Stock Exchange floor. This 'first come first served' approach proved very successful for Boral; it acquired 10 per cent of the Brisbane Gas Company in a matter of hours, and a further 20 per cent the next day. However, Rowell was persona non grata for some time among the Queensland business community.

Once Boral had a 30 per cent shareholding in the Brisbane Gas Company, Allgas Limited, the supplier of town gas to the South Brisbane Gas Company, made a counter-offer to fend off Boral's bid. Boral then notified the Queensland Stock Exchange of its intention to make an offer to buy Allgas as well. Rowell recalls a conversation with Griffin in which Griffin commented, `We'll catch the fisherman as well as the fish!'. Boral's action resulted in the tabling of The Gas Suppliers (Shareholdings) Act, passed by the Queensland government in 1972. This prohibited Boral from holding more than 12.5 per cent of Allgas - the fisherman had slipped the net. After litigation, Boral withdrew the takeover offer for Allgas which in turn dropped its offer for the Brisbane Gas Company, leaving the way open for Boral to finalise the takeover.

Griffin then said to Neal, 'The next thing to do is make a full takeover offer to all the remaining shareholders so that no-one has been disadvantaged by our "first come, first served" bid.' Boral did this, acquiring 100 per cent of the Brisbane Gas Company, providing Boral Gas with a capital city utility.

History of The Brisbane Gas Company

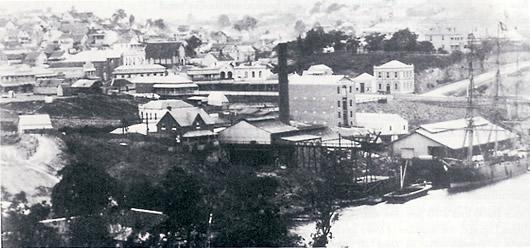

The Brisbane Gas Company was incorporated in 1864. Its first coal gas manufacturing plant was at Petrie's Bight on the river bank near the centre of Brisbane. At the time the city had a population of about 12,500 and kerosene street lighting which wasn't very efficient. Gas was assumed to improve street lighting, as well as offering shopkeepers and domestic homes the opportunity of much better illumination.

By 1883 Petrie's Bight had been outgrown and a 22-acre site was purchased on the river at Newstead. Here a larger coal gas plant, capable of producing 1.5 million cubic feet of gas per day, was erected. The plant began production in 1887. This site is still used by the company although gas production methods have changed dramatically. A thirty-inch cast-iron exit main, laid for the gasworks in 1887, is still in use. It took one hundred years for this pipe to be utilised to its maximum capacity.

In the 1880s a second coal gas plant was built on the south side of the river by the newly formed South Brisbane Gas and Light Co. Ltd, in direct competition with Brisbane Gas. This resulted in gas mains being laid independently on both sides of the river by both companies, which became very confusing. In those early days, the only way either company could be sure that they were supplying the people they were billing was to cut off their gas main at the end of the street and run down the street, making a note of the houses that blacked out. It is not known what Brisbane residents made of these lightning power cuts.

In 1889 common sense prevailed. The Queensland state government brought in a franchise agreement obliging both companies to restrict their operations to the side of the river on which their gas plants were located. In the early 1890s the gas lighting monopoly was threatened when electricity was introduced. However, the gradual decrease in the use of gas for lighting requirements was more than offset by the growing demand for gas for cooking and heating appliances.

In 1893, Brisbane experienced the first and worst flood in its recorded history and gas production was stopped for two five-day periods. The second major flood was in January 1974 and the erection of sandbag levies around vital production plant equipment at Newstead meant that Boral could maintain an uninterrupted gas supply to its Brisbane customers despite the natural disaster.

Up until 1965, the Newstead plant used coal for gas making. Initially supplies came by ship, from New South Wales and as far afield as England until it was established that the coal from nearby Rosewood and Ipswich was suitable. In 1965 a reforming plant was erected at Newstead which converted LPG into a product with the same characteristics as town gas. The LPG was brought in by road tanker. Rod Holmes, General Manager of Queensland Gas Corporation, joined Brisbane Gas Company in 1953 and was financial controller at the time of the Boral takeover in 1971. He recalls, `This was a precarious way to operate, particularly in times of road transport or refinery strikes'. Boral subsequently entered into a contract for the supply of naphtha gas from the refineries along the river at Hamilton. These refineries were connected to a pipeline so there was always a supply of gas available. To ensure a permanent gas supply to its Brisbane customers, Boral also bought a standby plant and two electricity generators to supply all the electricity required to keep the works plant in production.

Norman Hurll - A Big Turnaround

In 1967 Boral had been persuaded to buy a 50 per cent share in Norman J. Hurll and Co. (Victoria). This had originally been intended to be a silent shareholding and was a highly strategic move for Boral, as Norman J. Hurll had an agency for gas reforming plants from a European company and supplied these units to gasworks throughout Australia.

However, Norman J. Hurll was family-owned, and the company ethics were very different to those of a public company such as Boral. The two proprietors had very different views on management, and before long there was a major dispute between the parties.

By the end of 1970 Norman J. Hurll was operating at a loss and Boral management recommended it be sold off. However, the contract of sale was unattractive to Boral and Neal, with his experience as general manager of the Gas Supply Group, was asked to give his views on the company. Griffin sent Neal to Victoria to spend time looking at the business. His instructions were, `You can let the sale go through, you can close it down and not let the sale go through, or you can operate it - the decision is yours'.

Neal came back to Sydney at the end of the fortnight and reported back to Griffin that he felt the company, properly structured with some management changes, could make money, if it concentrated on what it knew best. Griffin said, 'Right, you're the chairman of the company,' to which Neal responded,

`I don't want to be chairman, as long as I have the authority to make the changes.'

Griffin countered, 'If we make you chairman of Norman J. Hurll and Co., there'll be no doubt about your authority.'

The family sold out and Norman J. Hurll became wholly owned and directed by Boral in 1972. Boral paid the company's creditors and recovered the tax losses on Norman J. Hurll within a year and a half.

By this time Boral had acquired the Brisbane Gas Company and Norman J. Hurll had been turned around. But there were problems with Glen Iris Bricks in Victoria, which Boral had acquired in 1970. As well as managing the Gas Division and Norman J. Hurll, Neal was put in charge of Boral's Brick and Concrete divisions.

In January 1972, Boral formally withdrew from its joint venture with Total by selling its 50 per cent shareholding in Total-Boral Limited to Total Holdings (Aust) Pty Ltd. This ended nearly twenty-five years of direct involvement with the oil refining industry.

Cyclone

In 1975, there was a sharp downturn in Australia's housing industry and it was realised that the company could become too dependent on the home-building market. During early 1975 Neal was looking for further means of expansion. Keith Halkerston, a merchant banker who had recently joined the Boral board, researched companies that were likely takeover targets. The Cyclone Company of Australia was on his list and Boral decided to make a bid for the company. Boral saw Cyclone's fencing products and rural buildings as giving them the diversification they sought and less dependence on the home building and the city construction business. Boral also felt that Cyclone's scaffolding operations would complement Boral's existing construction business.

Neal remembers the takeover well, because Griffin was seriously ill at the time and had not been in the office for five or six months. Boral prepared the takeover documents on the Friday, but sadly Griffin died on the Saturday and on Sunday a new set of documents had to be drawn up because he was no longer a director. The documents were served on Cyclone on the Monday morning. The company contested the takeover; the Cyclone directors unanimously considered that Boral's offer was too low and told their shareholders. Subsequently ARC Industries Limited announced its intention, subject to clearance from the Trade Practices Commission, to make an offer for the whole of the issued capital of Cyclone on terms that ARC Industries considered much more attractive to the shareholders than those offered by Boral (ARC Industries had previously made an unsuccessful bid for Cyclone in 1956). In a landmark case, the Trade Practices Commission refused ARC Industries clearance to make an offer, which prompted the company to abandon its bid. The Trade Practices Commission ruled that an acquisition by Boral would not result in any lessening of competition but that acquisition by ARC Industries probably would.

Cyclone and Tubemakers

Early in the Cyclone takeover, Boral had received acceptances for less than 10 per cent and it was obvious to Neal that the bid would not be successful. He arranged a meeting with Tubemakers' managing director, Jock Gosse. That company owned about 14 per cent of Cyclone and asked him whether they would accept Boral's offer. Gosse's response was that Tubemakers was not anti-Boral or anti-Cyclone, but that they thought they would wait until Boral got past 50 per cent and then make a decision on their shareholding. Neal told him that if every shareholder felt as he did, it would be impossible for Boral to get to 50 per cent! Neal told him that Boral did not propose to close Cyclone down; Boral proposed to expand the business and felt that the offer was worthy of support. Gosse then said, 'Well, I'll have to talk to the chairman, Sir Ian McLennan, it's up to him'. It was a Friday afternoon and Neal recalls going into Boral's monthly board meeting at nine-thirty on the following Monday and saying to his secretary, 'If a call comes through from Jock Gosse of Tubemakers, interrupt me in the board meeting'. This she did about an hour later. Neal left the meeting to take the call and was advised that McLennan had authorised Gosse on behalf of the board to accept Boral's offer. Boral jumped from a holding of around 10 per cent to 30 per cent, and the takeover was won. Until Neal retired, Cyclone continued to be a customer of Tubemakers and Australian Wire Industries because he felt that they had supported Boral at that crucial time. There was no request by either company that Boral do so, but Neal believed customer-supplier loyalty was important.

Around this time Neal first came to the attention of the Australian business media. In October 1975, when Boral began its steady list of takeovers by picking up Cyclone, the Bulletin described him as 'a plain-speaking man who "tells it as it is" and has little use for management jargon'.

Cyclone's History

Cyclone was formed in the early 1890s, when Leonard Chambers entered into a partnership with William Thompson to manufacture beekeepers' hives and accessories. They also imported and distributed queen bees, to improve the existing strain of Australian bees.

In the mid 1890s, Chambers read a small advertisement in an issue of a US beekeepers' journal that proclaimed the merits of a manually operated machine able to weave wire fencing directly onto previously erected fence posts. Envisaging the scope for such a fence in Australia Chambers contacted the manufacturers, Lane Bros, who had established the Cyclone Fence Company in the United States. Negotiations to secure the Australian rights were successfully carried out by mail and Cyclone Woven Wire Fence Company was established in Melbourne in 1898. Initially all the wire and pickets had to be imported from the United States as the Australian steel industry was non-existent.

By 1912 Cyclone was well established. However, Chambers was always on the lookout for new business opportunities and in 1913 embarked on a disastrous episode for the company. Again, while studying an American magazine he came across an advertisement for a 'home canning outfit' for fruit growers and market gardeners. It enabled fresh produce to be canned immediately, reputedly providing greater profit to the producers. Chambers decided to import the kits from the United States. It quickly became apparent that highly specific technical knowledge was necessary, as was a supply of cans. Some local producers were experiencing problems with the product, and Chambers decided that Cyclone would embark on a fairly bold course manufacturing its own cans and timber cases for packaging and marketing these products under the Cyclone name.

The 'home canning outfit' exercise came to an abrupt halt because it could not be guaranteed that the cans would be totally airtight when sealed. This resulted in the tins 'blowing', both in the hands of the customers and in Cyclone's warehouse. The company was forced to withdraw the product and dump its stock at a substantial loss and so Cyclone's canning venture came to an inglorious end.

Cyclone Pty Ltd was incorporated in 1914, just before World War I; soon afterwards the company, like many manufacturing businesses, experienced difficulties, particularly in acquiring supplies of raw materials. Deliveries of imported goods were extremely unreliable and the prices high - wire cost an exorbitant 7 pounds a ton.

In 1925 the company changed its name to Cyclone Fence and Gate Company Pty Ltd, more accurately reflecting its principal business activities. It survived the 1930s Depression without trading at a loss and in 1937 secured the Australian agency for tubular scaffold fittings manufactured by London and Midland Steel Scaffolding Co.

With World War II, Cyclone, with its expertise in the wire industry, was quickly requisitioned to provide supplies for military purposes. The wartime demands stretched the capabilities both of the company's plants and personnel to their limit. Consequently, by the time peace was declared in 1945, Cyclone's civilian trade had totally dropped off.

In 1947, after obtaining advice from the stockbroking firm Ian Potter and Co., the directors formally registered Cyclone Company of Australia as a publicly listed company. The new capital in the company was offered to the existing thirty shareholders and to the general public on a two-thirds to one-third allocation. Shares were offered to the public at an issue price of 1 pound with a premium of 1 pound and were eagerly sought.

In 1958, Cyclone decided to enter the aluminium window market, due to the increasing demand for this product. They also introduced a new range of hand and garden tools and expanded the scaffolding operations to Canberra to cater for the upsurge in building development in the federal capital.

Boral took over Cyclone in 1976. The window division was consolidated with the purchase of Dowell aluminium and timber windows in 1988. Dowell Australia Limited can be traced back to 1857. With well-established operations in all states, Dowell continues to trade under its own name.

In 1993, the Boral board decided to concentrate on its core businesses. The company floated Azon Limited and sold many manufacturing subsidiaries including Cyclone Hardware and wire meshing, as well as other businesses acquired over the years that were no longer strategically important. Boral did, however, retain the scaffolding and window businesses it had gained through the original takeover.

Thirty Years On

When Griffin died, O'Neill invited Peter Finley to become deputy chairman. Finley explained to O'Neill that he was already fully committed, and O'Neill replied, 'Well look, there's not too much to do as deputy chairman. I would like you to accompany me to the different states, see all the operations and meet the people.' Finley agreed to do this and looked forward to a long period as deputy chairman of Boral. Sadly, O'Neill died within a year and Finley was elected chairman in July 1976. It was Boral's thirtieth anniversary and that year the company made a profit of $20 million, though there was still plenty of room for further expansion.

Boral Changes Its Image

The year 1976 produced another landmark for the company: this was the year the now familiar gold and green logo was adopted. This innovation was announced in the annual report as follows:

Corporate Identification Program

The Boral Group is made up of many companies operating in a number of diversified extractive, manufacturing and service activities.

Whilst, legally, these companies are part of Boral Limited, they have always traded under their own names and have been identified by their own symbols and insignias.

Now, because of the size and diversification of Boral in Australia, we believe that it is time that all of the companies which give Boral its size and diversification, be visibly identified with the parent.

During July and August, 1976, we have changed the names of many of our companies, generally by adding the prefix Boral to existing names and in some cases simplifying the name to more properly reflect the activity in which the particular company is involved.

Boral Limited and its many subsidiaries have also adopted a new corporate symbol and colour scheme. This symbol and colour scheme will be used on signs, vehicles, stationery and uniforms throughout Australia and through the symbol all Boral companies will present a single unified face to the Australian public.

As well as creating a strong sense of belonging among our employees, we believe that this move will have a most significant effect on Boral marketing in the future.

| Boral 1976 | |

|---|---|

| Total Sales Revenue | $244,860,000 |

| Net Profit before tax and depreciation | $29,160,000 |

| Net Profit after tax and depreciation | $12,494,000 |

| Assets | $250,059,000 |

| Number of Shareholders | 29,995 |

| Dividends paid | $7,906,000 |

Holt and Associates, a small advertising company that is now part of Clemengers, was approached by Malcolm Yell, Boral's marketing manager. Yell asked them to come up with a corporate campaign for the Boral Group. The advertising company could see that Boral could capitalise on the huge marketing opportunity, unifying all its brand names and creating one strong image. Holt and Associates, knowing Boral's lack of experience in this area, came up with a succinct two-page strategy and Neal took this proposal to the Boral board. They heard nothing more until four months later when Neal rang John Pitt, Boral's account executive, to tell him that the board had approved the plan and to ask whether they could have the new logo design in one week's time.

Holt and Associates came up with the concept of a flag - this type of logo hadn't been seen in Australia before. They chose the green and gold as a departure from the traditional red and blue of the Australian flag (these colours were also associated with many petrol companies at the time). Green and gold were recognised as Australia's sporting colours. Neal approved the simple design with the comment 'We can always change it if it doesn't work!'. But work it did, and thirty years later it has not dated.

Australian Gypsum Industries

The next significant takeover after Cyclone came about two years later with the acquisition of Australian Gypsum Industries in 1978. Because of the worldwide oil price crisis in the 1970s, Boral had been looking at insulation as a possible product. The first leaps in the price of oil occurred in the mid- 1970s, followed by a further leap in 1978. These oil price movements alerted the world community to the importance of energy conservation. Australian Gypsum Industries had an insulation division and Neal was also interested in its gypsum board manufacturing in relation to Boral's construction activities.

Finley recalled, 'Australian Gypsum, like many companies of the era, had a number of directors on the board who believed in having a lot of Commonwealth Bonds on the balance sheet as they were very liquid. They also believed in not having any borrowings. For the times (the early 1970s) this wasn't a bad strategy, but in subsequent years it worked against them, because as soon as a company has an attractive balance sheet it becomes an attractive takeover target.'

In early 1978, press speculation was mounting about Boral being the likely suitor for Australian Gypsum. Neal flew to Hong Kong as a smokescreen for Boral's offer. His strategy worked; the overseas trip was interpreted as Boral's lack of interest in buying the plaster products group. With media attention effectively diverted, Neal directed the takeover from the South China Sea. At the time, the $55 million takeover was the largest in Australian business history, indicative of the escalation of acquisitions during the period. Boral moved from a few per cent shareholding to more than 54 per cent in three working days. The plasterboard side of the business turned out to be of particular benefit to Boral, tying in as it did with the company's other building material products. Ironically, the insulation side of the business was eventually sold, even though this had been the focus of Boral's initial interest.

Australian Gypsum Industries History

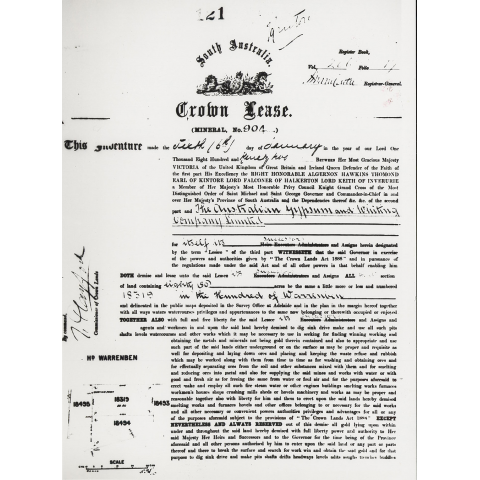

In 1892 the Earl of Kintore, Governor of Her Majesty's Province of South Australia and the Dependencies, signed an indenture granting the Australian Gypsum and Whiting Company Limited and its successors 'full and free liberty . . . to dig, sink, drive, make and use all such pits, shafts, levels, watercourses and other works which it may be necessary to use in seeking for finding, winning, working and obtaining the metals and minerals not being gold therein contained'.

This lease permitted the first gypsum mining operations to begin at. Marion Lake in the Hundred of Warrenaben on Cape Yorke in South Australia.

The name 'Australian Gypsum' was derived from a Sydney company that began producing plaster more than fifty years before at Duck Creek near Parramatta in Sydney's west. Initially its gypsum supplies came from Roto, in western New South Wales, but in the early 1920s leases were obtained at Lake Macdonnell in South Australia where gypsum was bagged for shipment to Sydney.

During the 1920s four major gypsum and plaster companies operated on the Yorke Peninsula. Financial difficulties caused by the major decline in building activity in the 1930s Depression, led to talks between these companies which culminated in the merger of their businesses under the name Australian Gypsum Products Pty Ltd. This rationalisation of the group operations meant that all mining activities were stopped except on the Marion Lake deposit. This period of consolidation saw an improvement in trading results from a loss of 3500 pounds in the year ending 30 June 1931 to a 110,000 pound profit in 1939.

To meet the demands of a buoyant market, a new plaster mill was established in the Sydney suburb of Camellia in 1930. Boral still produces plasterboard from this site. The United States armed forces took over the factory between 1942 and 1946 as a torpedo repair base.

In 1939 internal reorganisation saw the establishment of Australian Plaster Industries to conduct plaster manufacturing for the company. On the eve of World War II, Australian Gypsum Products reached agreement with the United States Wallboard Manufacturing Company to purchase a plasterboard plant. This new product revolutionised the plaster industry; fibrous plaster manufacture soon became obsolete with the introduction of the paper-covered plaster sheet. The war delayed the construction of this new plant until 1946 and production and sale of Victorboard' plasterboard did not begin until 1948.

Boral has only two major Australian competitors in the gypsum market - CSR and, more recently, Pioneer. Before Pioneer entered the market Boral and CSR were the only operators. Both companies had major gypsum leases in South Australia and manufacturing facilities in the eastern states. In 1983 Boral and CSR formed a joint venture company, Gypsum Resources Australia Pty Ltd. This company mines and transports the gypsum as required by the partners. In 1984, a modern bulk carrier vessel, MV Kowulka was commissioned to maintain the flow of product to the manufacturing plants and an associated company in New Zealand.

Increasing the Capacity of Fiji Gas

During the late 1970s Boral's gas division had three sea tankers delivering LPG to Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands. Although these operations were well established, Neal was concerned about the future viability of one of the ships, Fiji Gas. The Australian economy had moved into an inflationary period since the mid-1970s and crew and oil costs were on the rise, but the cargo-carrying capacity of the ship was already at maximum.

Neal was travelling to Papua New Guinea on the Fiji Gas ; it was a fairly clear night and they were in the Coral Sea. Neal said to the captain on the bridge, `What would be the effect on this ship if we lengthened it by, say, fifty feet?'.

The captain replied, 'Well, it would improve it. It would have better sea- keeping qualities, and, of course, more capacity could only be an advantage.'

In 1978 the Fiji Gas was consequently lengthened by about fifteen metres, done by cutting the ship in half and adding a new section in the middle, incorporating an additional 500-cubic-metre--capacity LPG tank. Neal recalls, `The whole project was very well planned, both by the personnel of the Gas Group and the shipbuilders who prefabricated the new section. The cutting and fitting were carried out in dry dock in the matter of a few days. Gordon Leslie, General Manager of Boral Gas, coordinated the project.