Falling Out with Caltex

Problems with the supply of crude oil began in 1948 and continued into 1950. The directors' report of 21 November 1950 summarised the events.

Shortly after the formation of Bitumen and Oil Refineries (Australia) Limited a contract was entered into with the California Texas Oil Company Limited for the supply of very heavy residual oil suitable only for the manufacture of bitumen. To this was added a percentage of petrol so as to make this oil sufficiently fluid to be handled by tanker. This contract was successively assigned to Caltex Oceanic Limited and on 23 August 1950 to Caltex (UK) Limited.

A few months after operations commenced in 1948, it became obvious that on the basis of producing and selling bitumen only serious losses would be incurred which, if continued, would have resulted in the Company being a complete failure.

Consequently, arrangements were made with the California Texas Oil Company Limited to supply a synthetic crude which, as well as containing the heavy residual oil for the production of bitumen, also contained diesel oil and fuel oil. This type of synthetic crude oil came into use in April 1949.

On 18 September 1950 Caltex (UK) Limited, to which Company the agreement had been assigned, gave notice of termination of supply of the new type of crude.

If other arrangements had not been made Bitumen and Oil Refineries (Australia) Limited would again have been reverted to the impossible position of being dependent on the production and sale of bitumen.

A long-term contract has been entered into with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company Limited, on favourable terms, for the supply of whole crude oil and the provision of tankers. Whole crude is crude oil straight from the well and not previously partly processed as is synthetic crude oil. Deliveries under this contract are to commence in February, 1951.

Caltex (UK) Limited applied to the Equity Court for an injunction to restrain the Company from entering into this contract, but abandoned its application on the day set down for hearing of the case.

Meanwhile, several things were happening behind the scenes. Firstly, there was a dispute over the definition of crude oil under the original agreement with Caltex. The bulk bitumen market was not as buoyant or as profitable as had been anticipated so that, while there was strong local demand, potential customers did not have the receiving tanks necessary for bulk bitumen and still wanted to be supplied in 44-gallon drums.

Griffin, as the new managing director, became interested in the oil market generally and how it was structured. Thumbing through the oil publications of the day he discovered that the synthetic crude oil being sold into Australia was actually a waste product and, had there not been a market for it outside America, would have simply been dumped. What really troubled Griffin, however, was the revelation that Bitumen and Oil Refineries was being charged the same amount for this inferior synthetic crude as for whole crude oil, a far superior product.

Secondly, Caltex was vehemently opposed to Bitumen and Oil Refineries' proposed installation of a platformer - a catalytic reformer - that produced petrol from the heavier end of the synthetic crude oil supplied by Caltex. Caltex was trying to minimise the amount of petrol Bitumen and Oil Refineries could make, as it was obliged under the agreement to take it back. Caltex did not want this additional petrol because its own refinery at Kurnell was coming on line. The platformer could also upgrade some of the whole crude oil into motor and aviation fuels.

Both these disputes came to a head just before the 1950 Annual General Meeting and it became apparent that there would be a contested election of directors. Caltex's plan was to oust Griffin and appoint an Australian of their choice to the board; this Australian director and three nominees would give them support from four out of seven directors and total control of the Board. They put forward Telford Simpson, the senior partner of Minter, Simpson and Company, Bitumen and Oil Refineries' solicitors at the time.

Griffin approached solicitors Murphy and Moloney for independent legal advice on the original agreement with Caltex. Harry Morrissey asked Gerry Wells, a partner with the firm, to examine the legal document. It became clear that there was a flaw in the drafting of the supply agreement. It called for Bitumen and Oil Refineries to buy the whole of its oil supply from Caltex, but 'oil' was defined very narrowly. If Bitumen and Oil Refineries did not need 'oil' under the contract's definition, it was free to buy its crude oil supply from whoever it chose. Griffin could buy genuine whole crude oil on the open market rather than accepting the inferior synthetic crude that Caltex was supplying.

To present Bitumen and Oil Refineries' case, Wells asked Ted Webb, the refinery manager, to separate and bottle the components of Caltex's synthetic crude as well as the components of genuine whole crude. The synthetic crude was presented in two bottles, one of which contained bitumen and the other petrol. However, when the whole crude oil was broken down, it separated into about thirty bottles of the product's different components. The problem with the quality of the synthetic crude oil became obvious. Wells said, 'If you looked at two bottles against thirty bottles you would see you were talking about apples and pears - the synthetic crude oil and the whole crude oil were entirely different products'. Bitumen and Oil Refineries' answer to Caltex's claims was simple: if it wanted bitumen and petrol it would buy it from Caltex, but if it wanted whole crude oil it was free to buy it on the open market.

When Caltex heard of this development, they intensified their campaign to get Griffin off the board and assume control of the company. At the time, defying Caltex appeared a formidable task. The company already had 40 per cent of the voting power in one hand which meant total control. Bitumen and Oil Refineries was one of the first Australian companies to have a one-share, one-vote system rather than operate on a sliding scale. The company's Articles of Association also contained an oddity whereby debentures issued to secure loans could have voting rights. Gerry Wells identified this as a way of neutralising Caltex's votes, but it was crucial that a debenture issue should be made for genuine reasons.

Tom Murray, who succeeded David Craig as chairman of Bitumen and Oil Refineries, was also a director of the City Mutual Life Assurance Society Limited. He could see that if City Mutual financed the loan for the platformer, this could have significant benefits to Bitumen and Oil Refineries. Under the loan agreement the City Mutual would require one vote per pound of debenture money. The platformer cost about 400,000 pounds, which happened to equal 40 per cent of the voting power of Bitumen and Oil Refineries. City Mutual's vote would exactly balance that of Caltex.

There were two shareholder meetings - an Annual General Meeting and a Requisitioned Meeting - designed to give Caltex dominance of the Board and replace Griffin as a director and chief executive. The final, crucial meeting was held in the Assembly Hall in Margaret Street, Sydney, and almost every public shareholder turned up. It was a very dramatic occasion, with the meeting lasting nearly all day. At the end a proxy battle took place because the City Mutual's votes nullified the Caltex vote. Wells recalls, 'And a proxy battle it was; there was an enormous flurry of paper; votes were bought and people got money for them and then changed their proxy. It was quite an exciting time.' The Australian shareholders ultimately succeeded; Caltex was defeated.

Having legally established that the company was not under obligation to buy crude oil solely from Caltex, Griffin entered into a long-term contract to buy whole crude oil from the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, now better known as BP. In 1951, Caltex UK applied to the Equity Court for an injunction to restrain Bitumen and Oil Refineries from entering into this contract. Wells recalls, 'The case was never heard. They abandoned the application on the day set down for the hearing.' A somewhat ironic twist to these events was that a year later, in 1951, the Annual General Meeting had to be adjourned for lack of a quorum; the Caltex proxy failed to reach the meeting in time.

Petroleum and Chemical Corporation

In 1954 Bitumen and Oil Refineries floated Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Australia), in which it had a controlling interest, to erect a high- temperature cracking plant at Silverwater on the Parramatta River in Sydney's west. This plant would ensure the disposal of residual oils from the Matraville refinery, as well as enabling Bitumen and Oil Refineries to expand into the petrochemical field. The cracking plant took the heavy end of the crude oil and converted it into liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). At one stage Bitumen and Oil Refineries was supplying one-third of Sydney's gas supply because of a deal with Australian Gas Light Limited (AGL). To facilitate this supply, Petroleum and Chemical Corporation built a gas pipeline from Silverwater to Mortlake where AGL was situated. The cracking plant's LPG was used to supplement AGL's own gas supply which it was making from coal and coke.

That same year, following negotiations With the Queensland government, Queensland Oil Refineries Pty Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary, was incorporated. This company was granted a thirty-year lease of 40 acres at Hamilton, close to Brisbane on the river, to construct a refinery and associated facilities. It consisted of a simple splitting unit to produce bitumen, and a road-surfacing contract operation was attached to it.

Meanwhile, the Matraville refinery was expanded with the addition of a desulphurisation unit. The 1954 annual report explained:

Use of diesel engines for many purposes has grown at a rapid rate in post war years and manufacturers of such engines for some time past have emphasised to their customers the desirability of using low sulphur content fuel.

It has been decided to install most modern equipment for the catalytic desulphurisation of our diesel oils and our product then will compare more favourably with any offered by competitors.

Fire at Matraville

In an endeavour to maintain the highest of standards at the Matraville refinery, fire drills were carried out. Every second Wednesday at eleven o'clock, the fire alarm hooter would sound. All the mechanics at the refinery garage were trained to test forty or fifty small gasoline fire pumps that would pump foam and salt water around the refinery in case of fire. As soon as the fire alarm sounded, they made sure that all of the engines' spark plugs were clean and that they would start up with one pull (as a lawnmower should). While this was happening a number of personnel inspected the fire protection equipment.

The refinery also had a hand-drawn fire fighting vehicle about the size of a lorry. Although it was hand drawn, it was quite a sophisticated piece of equipment, with enough extinguishers and fire fighting gear to allow refinery personnel to contain a blaze until the fire brigade arrived. But instead of having an engine, which might have been difficult to start in an emergency, it was designed with shafts in front and at the rear where men could fit. Four would pull from the front while four pushed from behind. This vehicle would, in theory, be taken to the scene of the fire. At its widest point, the refinery was only about four hundred yards wide. During the fire drill eight men would man the vehicle and run it up and down the road a few times. Jim Cornell remembers, 'It looked beaut! The fire drills went on for two or three years and they were always perfectly executed.'

The fire alarm went off one Tuesday at about eleven o'clock. Griffin said, 'Those blokes down there don't even know what day it is! It's eleven o'clock and it's Tuesday - they think it's Wednesday. For God's sake Jimmy, get in your car and go down and straighten them all out.' Cornell calmly finished reading the paper, intending to go a little later for a word with the refinery manager and crew. But he happened to glance out the window, saw a great cloud of black smoke belching from the bitumen section of the refinery and suddenly realised they had a real fire on their hands. Following the fire drill procedure, all the engineers from the garage ran over to start the pumps, which started perfectly. But once the salt water and foam had been spurting out for about five minutes, all the streams stopped: nobody had thought to refill the pumps. The men assigned to the fire fighting lorry all did their jobs perfectly, except that the fire was in the bitumen section. This was the highest point on the refinery and they couldn't haul the lorry up the hill to it. The rest of the men went to put on their fire protection gear and equipment, but nobody had realised that the employee in charge of it always kept it under lock and key. He was on leave and had taken the keys with him. The local fire brigades from Botany and Randwick were called on to save the day. The fire was contained but the bitumen section was totally burnt out; the control room and instruments had to be replaced at considerable cost.

The Safety Film

Increasingly mindful of plant safety, management had decided to produce a film to demonstrate basic safety procedures when using potentially dangerous equipment. One film was intended to encourage staff to wear goggles when they were using the grinding machine. The film script showed a worker grinding without goggles, getting a steel splinter in his eye and being taken by ambulance to hospital. The scenario was then repeated, except this time he was wearing the safety goggles. They were filming this second segment and the 'talent' was asked to turn and smile at the camera, demonstrating how safe and secure he was with the goggles on. As he turned to the camera, he lopped his little finger off. The use of a grinding machine could be dangerous.

Industry Developments in the Late 1950s

Boral in 1956

| Net profit before tax and depreciation | £803,761 |

| Net profit after tax and depreciation | £465,711 |

| Assets | £6,322,163 |

| Dividends paid | £300,000 |

In 1957 the Federal government removed the import duty on petrol. Crude oil had not been discovered in Australia although exploration was taking place. The government's action reduced protection of the Australian oil refining industry, increasing the cost of converting crude oil.

The year 1957 was also an important one for the gas industry in Australia; bottled LPG was first produced in Australia by Mobil's Altona and Shell's Geelong refineries in Victoria. The process involved bottling the LPG (a refinery by-product) under pressure; on release it would completely vaporise. Areas remote from town gas supplies now had access to this energy resource.

Bitumen and Oil Refineries' profit for 1958 was adversely affected by the elimination of petrol import duty, compounded by the general weakness of the selling price for refined oils on world markets that year. The selling price was based on overseas quotations, which in 1958 fell substantially. Meanwhile the Matraville refining capacity had increased to over 15,000 barrels of crude oil per day.

In September 1959 the Federal government adopted the Tariff Board's recommendation that customs duty on petrol be reduced by one halfpenny per gallon, an action that further lessened Australian oil refiners' protection in their own market. Despite this, the Matraville refinery was still expanding. A fluid catalytic cracking unit had been installed at a cost of 2 million pounds. It converted heavy oil to gasoline and increased gasoline production allowing a better balance of refinery products to market demand.

Improved Refinery Training

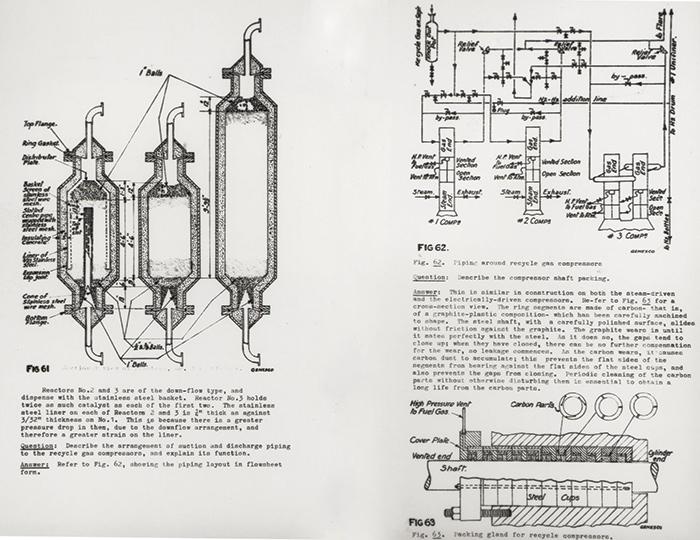

The company's early attempts at occupational health and safety were not very professional. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, refinery experts were brought in from the United States to help train operating staff in safety and refinery procedures. Andy Hanson and Robert Whitaker spent twelve months lecturing and training staff. Whitaker put together a highly technical refinery operator's manual with the following foreword:

The Refinery Operator's Training Manual 1961 Introduction

This book has been written, printed, and distributed to you - that is, to all BORAL operating staff - with only one purpose in mind. (That is, to make better operators of you.) A famous saying goes: 'The man who knows how will always have a job, but the man who knows why will always be his boss'. We believe that careful reading of this book, with frequent referring to it as you progress during the years with BORAL will not only tell you how, but also why. In fact, you will start to learn why before you learn how, because in this manner you will have better understanding. With better understanding will come increased confidence; and with increased confidence will come improved operating and fewer expensive errors: and promotion for yourself cannot be given to you if you are not prepared.

A man can be a good operator without knowing all the reasons for what he is doing; and he can also learn all the theory there is and not make a good operator. Being a good operator involves constant alertness, and much hard work in conscientiously carrying out the daily routines, as well as cooperation with the rest of the staff with whom you deal and with the other branches of the refinery. AS YOU BEGIN TO UNDERSTAND MORE ABOUT YOUR PLANT AND EQUIPMENT, HOWEVER YOU WILL BE MORE ABLE TO OPERATE IN SUCH A MANNER THAT TROUBLE NEVER GETS STARTED. FORESIGHT WILL BEGIN TO TAKE THE PLACE OF HINDSIGHT.

Some important sections of the book deal with the carrying out of the laboratory tests, and with the mechanical features of the refinery equipment. These are not given so that you can become laboratory testers, or maintenance fitters, or so that you can supervise their work or criticise their technique. Knowing these things will give you an understanding which will inevitably lead to better operation, so that products come on test faster and stay longer, and the equipment is operated without being abused or mishandled.

This book incidentally, is not meant to be read as if it were a novel. Almost every paragraph of every lesson requires careful study and thought. Please read the section `How to use this Manual, before starting to read Section A.

Robert Whitaker