Branching Out Overseas

Boral's intention of getting into the United States market went back a long way. Griffin had toyed with the idea but never really took the plunge. Various senior staff recalled that even Western Australia was too far away for Griffin. However Neal's interest in the United States was raised right from the beginning.

On Griffin's retirement, the financial press had speculated that Boral, under Neal's leadership, would soon expand overseas. And indeed, Neal visited the United States virtually every year after he became chief executive, looking for business opportunities. However, he was very conscious of the fact that a number of Australian companies had tried to move into the United States market and 'stubbed their toes'. Neal wanted to be sure that when Boral made the move, it was the right one.

When Neal took over in 1973, serious problems began to emerge in the Australian economy - a sharp increase in wages and downturn in business activity. In this uncertain climate, the Boral board considered it prudent to postpone moves overseas until the domestic situation stabilised. This did not happen until 1978.

Amalco, a Hawaiian-based company manufacturing concrete products, entered the Australian market in the 1970s. It acquired concrete product factories in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. The Adelaide factory, called Hollostone South Australia, had just bought a concrete roof tile machine with the intention of competing with Monier in that state's housing market. But Amalco in the United States fell on hard times and needed to sell off some of its assets. Tipped off about this, Neal approached Mr Sykes, Amalco's chief executive, and negotiated to buy its Australian concrete products operations.

At the time, Boral scarcely took into account the South Australian roof tile plant which was worth about a million dollars but wasn't working. Evan Evans was the manager of Hollostone in South Australia, and, once the takeover was complete and the problems with the machine came to Boral's attention, he was assigned to look into the tile plant. He reported back to Neal saying, 'I believe that the problems with this machine can be resolved. It will take me a year to get the tile plant working but I believe I can guarantee at the end of the year it will be profitable, and it will give Boral a good position in the roof tile market in South Australia, which Monier seems to have sewn up.' Neal asked what the exercise would cost. It was clear that the losses would be in the vicinity of $200,000. After some thought Neal replied, 'Well, we'll back you for a year and see what you can do.'

Within the year Evans had the concrete roof tile machine modified and working. The plant was producing tiles and giving Monier some real competition in South Australia. It wasn't long before Boral had a sizeable share of the Adelaide roof tile market. About a year after the tile plant had been modified the engineer who had designed the roof tile machine came out from the United States and inspected his machines here. He called Neal when he was passing through Sydney to compliment Boral on the Adelaide operation, telling him that the machine there was working better than any others he had built.

A year after Boral took over Amalco's Australian interests, one of the company's factories in California was losing money and they approached Boral to go in with them on a half-share basis. California Tile Inc. had two roof tile machines that were the same as those in the Hollostone factory. Neal, Evans and Peter McDonnell, Boral's commercial manager at the time, went over to inspect the operation. Evans advised them that the problems with the roof tile machines resembled the problems experienced at Hollostone. Boral acquired 55 per cent of California Tile Inc. in 1979, and this was the linchpin of Boral's expansion into the United States. Within a year, the business had turned around and the plant was operating at a profit. Boral bought the company outright from Amalco six months later. To this they added a new tile-making plant in San Antonio, Texas, and further consolidated in the United States by acquiring a third tile plant in California.

When Boral expanded into the United States, the concrete roof tile business was relatively new in America because Americans had a tradition of using timber shakes or shingles. Particularly in California, a state subject to bush- fires, these represented a safety hazard. Shortly after Boral bought California Tiles Inc., timber shakes were outlawed in all new construction in that state and concrete tiles took a substantial share of the market. When Boral bought California Tiles Inc. outright in 1980, concrete tiles had only a 5 per cent share of the Californian roof tile market. They now account for 75 per cent.

Almost overnight, Boral had become the second largest manufacturer of concrete roofing tiles in the United States. The investment had amounted to only a few million dollars and it was a relatively small market. Boral did not want a presence in the United States just for its own sake, and the board decided to allocate 10 per cent of the total group assets, roughly $50 million, to invest there further.

Merry Bricks

The industry in which Boral chose to invest was bricks, and the company acquired Merry Companies in 1980. The operations were based in Augusta, Georgia, in the heart of the Deep South. Boral's chief corporate strategist, Brian Saunders, who had toured the United States with Neal researching companies, remembers the first Merry Bricks board meeting he attended. It was standard practice to say prayers before opening the business proceedings. He said, 'They were prayers right to the point - "Please Lord help us meet our forecast budget" - and the like. It was very different to the laid-back attitude we encountered in California.'

Merry Companies History

Merry Brothers Brick and Tile Co. first rented a brickyard in 1899. Ernest and Walter Merry left their Georgia farm that year bringing mules, a wagon and a load of cordwood. They joined forces with Arthur Merry, who had borrowed $1500 against his life insurance policy.

A friendly contractor kept the fledgling business from going under by purchasing the first kiln of bricks. In 1903 the Merry brothers bought land of their own on the outskirts of Augusta and constructed their first production facility. At about the same time Arthur and Ernest Merry bought out Walter Merry, who chose to pursue other interests.

The company prospered until the Great Depression when, ironically, Merry Brothers made one of its most progressive steps. Like most companies, Merry Brothers found itself with a great deal of slack time. The brothers decided to make the most of the situation and set about becoming `efficiency experts' in all aspects of their business. They greatly increased the quality of their products and plant productivity grew by 40 per cent without any increase in costs, personnel or equipment.

In 1940 the Merry brothers embarked on another development - Merry Shipping Co. However, World War II delayed this venture for several years. After the war Merry Shipping bought two barges and a tug and began plying the Savannah River between Augusta and Savannah, where the company bought waterfront property and built a terminal.

An aerial view of Merry Bricks Plant 2 in the 1950s.

The postwar boom brought prosperity and industrial expansion to the USA, and Augusta was no exception. Merry Shipping played a vital role in this growth, giving local industry an additional mode of transport for raw materials and finished products.

In 1959 the second generation of the Merry management decided to offer stock to the public, extending ownership outside the family for the first time; sales had exceeded production.

In September 1966 Merry embarked on a diversification campaign, purchasing a concrete block operation. In 1967 Merry Land and Investment Co. was set up as a wholly owned subsidiary to handle the use and development of company owned land that was not needed for the brick operations.

In 1968 stockholders approved a corporate name change to Merry Companies Inc., considering that this expressed the company's role of being a diversified supplier of space enclosure materials to the building industry.

The 1970s saw a period of expansion for Merry Companies, with Guignard Brick Works, Georgia-Carolina Brick and Tile Company and Dorchester Brickworks becoming separate divisions of the larger company.

Guignard and Georgia-Carolina Brick and Tile Company

Thomas Jefferson was President of the United States and the city of Columbia was just a village when James Guignard opened his brickyard high on a bluff overlooking the Congaree River in 1803. As surveyor- general of South Carolina from 1799 to 1808 his father John Guignard had surveyed Columbia's original streets.

Guignard Brick Works is the oldest brick company in the United States. It operated continuously, privately or commercially, for more than 180 years except for two brief periods: from 1865 to 1866 just after the Civil War, and during World War I, when lack of coal forced the plant to shut down.

Twenty years after Sherman's march through Columbia, Gabriel Guignard settled at Still Hopes, the family plantation on the Congaree River and reopened the business that had been founded by his great-grandfather.

The company, owned by the family, operated until 1955. In 1974 Guignard moved to new headquarters at Lexington, South Carolina. In October 1976 Guignard Brick Works management reached an agreement with Merry Companies Inc. that Merry would lease the Guignard Brick Works and other related assets.

The Georgia-Carolina Brick and Tile Company, which Merry acquired in the 1970s, was situated close to the Savannah River, where it was vulnerable to the springtime flooding which occurred once every few years.

Eugene Long, who in 1918 joined that company as a fifteen-year-old stenographer recalled John Greenwald, a manager in the mid-1920s. Greenwald was manager of Georgia-Carolina Brick's Plant Number Four in 1929 during a particularly bad flood. Though Greenwald was quite adept at brickmaking, his command of the English language wasn't quite as good; he had been born in Germany. Describing the damage at Plant Number Four, Long recalls him saying, 'My nice fine new office, mit the iron safe together vent down in the middle of the river out!'. During the peak of the flood the water reached the top of the kilns and Greenwald described it thus: 'The vater came so soonly up, my men dumb the trees and almost perished to death!' Plant Number Four, though considerably damaged, eventually resumed operations.

During the 1970s Merry Bricks also developed a process for mixing sawdust and clay to cut the weight of its bricks by 25 per cent. By 1979 the lightweight bricks made up 90 per cent of total production. The benefits of this development were substantial; it allowed the company to reduce shipping costs by 40 per cent and Merry went from being a major brick manufacturer in south-eastern USA to a national manufacturer and distributor.

The company also found another money-saving use for sawdust - a timber industry waste product - using it to fuel its brickmaking ovens. By 1979 three of Merry's six brick plants had been converted from fuel oil or natural gas to sawdust power.

In 1981 Merry Bricks expanded into Maryland, purchasing the Baltimore Brick Company established in 1827 when a group of enterprising gentlemen in a local tavern recognised that city's growing demand for building materials. This enterprise was known as Baltimore Brick Manufacturing and Export Company.

At the end of the nineteenth century, brick manufacturers were scattered throughout the city. Twenty-two of these firms grouped together and decided to centralise their operations; among them was Baltimore Brick Manufacturing and Export. This merger was incorporated as the Baltimore Brick Company in 1887.

At the turn of the century the Baltimore Brick Company owned 200 mules, employed in carting 500 bricks per load. At the time the average cost was US$8.00 per 1000 bricks. Over the years Baltimore Brick closed its plants throughout the city and it now operates from a location in Maryland.

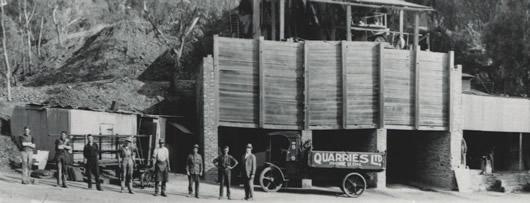

Quarries Industries Limited

Quarry Industries was the jewel in South Australia's quarrying crown, and Boral had never been very strong in quarrying or concrete in that state. Griffin had made an abortive offer for Quarry Industries in 1971-72. Boral had been severely rebuffed, receiving only 3 per cent acceptances and at the time Boral had not been at all popular with Quarry Industries. In 1980 Neal received a telephone call from Bruce Macklin, one of Boral's non-executive directors, saying he understood that Quarry Industries felt threatened by Pioneer, Bell Basic Industries or BMI, or a combination of them all. Macklin felt that it was looking for a 'Big Brother'. During the Christmas break of 1980, Neal went to Adelaide and met Don Laidlaw, who had been appointed chairman of Quarry Industries in 1979, to discuss the situation.

Laidlaw had noticed that McMahon Constructions, a small public company in civil contracting, had been steadily purchasing Quarry Industries shares for about twelve months and had acquired about 10 per cent of the company. Laidlaw suspected it was acting for somebody else, because he didn't believe that McMahon was large enough to be interested itself. It turned out that the shares had been pledged to Robert Holmes a Court's Bell Basic Industries. Laidlaw had suspected that Holmes a Court was interested because, having recently acquired Bell Basic Industries in Western Australia, he was keen to expand into the eastern states in quarrying and concrete. During early 1980, Laidlaw had ascertained that Pioneer Concrete had also been buying up Quarry Industries shares.

At that initial meeting Laidlaw asked Neal whether Boral would be prepared to buy 20 per cent of Quarry Industries to stave off Bell Basic Industries and Pioneer. Neal said, 'No, but if you would be prepared to sell 51 per cent of the company, I will talk to my chairman.' The upshot was that Boral made a takeover offer for Quarry Industries that was hotly contested by both Bell and Pioneer. Because of the high-profile personalities involved, the takeover received a lot of media coverage.

Holmes a Court brought an action in the South Australian Supreme Court to try to stop Quarry Industries transferring shares to Boral. This was thrown out of court and Boral had 78 per cent of the company on the last day of the share offer. Pioneer then bought Bell Basic Industries' shares in Quarry Industries. Laidlaw believed Pioneer still wanted to buy the company. Not wanting to be seen to be competing against Boral directly, Sir Tristan Antico, Pioneer's chief executive, had come to an arrangement with Holmes a Court. Antico was confident in any event that Boral would buy up Pioneer's 20 per cent holding to tidy up the acquisition. Neal discussed this prospect with Laidlaw, who advised him not to bother, as he was satisfied that Quarry Industries could live quite happily with Pioneer as a minority shareholder.

For a number of years, Antico, to show his annoyance at this, would get two Pioneer executives to nominate for the Quarry Industries board; the Boral representatives always voted against them. Boral had to handle this situation with some care because it had restricted voting rights in Quarry Industries' Articles of Association. The Boral representatives and Pioneer nominees would travel to Adelaide for the Annual General Meeting on the same plane, have lunch together, attend the meeting at which Boral would vote against the election of the Pioneer executives. Then they'd all get in a car and inspect the quarries before taking a plane back to Sydney - as Laidlaw comments, 'Having a day in the country to satisfy Sir Tristan Antico that they were looking after his interests'. It was not until Antico retired that Pioneer finally sold its shareholding in Quarry Industries to Boral in 1994.

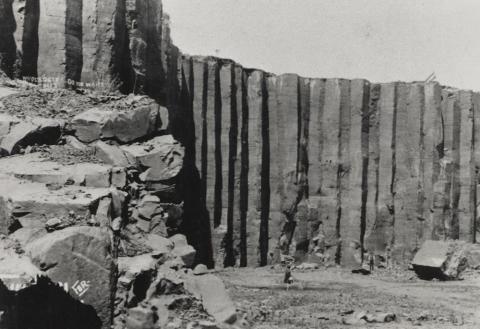

Stonyfell Quarry

One of the businesses Boral now owned, once Quarry Industries had been acquired, was Stonyfell Quarry in the Adelaide Hills. Establishing the date of the opening of the quarry is no easy task. The Record of Mines summary card from the Department of Mines states that it was opened in 1837 by James Edlin to supply slate and building stone. This would have been on a portion of the land now known as Stonyfell Quarry as various sections of land were used for different purposes over the years. These enterprises began independently and ad hoc, and often went undocumented. There are also several conflicting definitions of the area of Stonyfell Quarry, when differing names and dates surface.

In 1858, Henry Clark purchased a section of what is now part of the Boral quarry. He and his fiancé Annie Martin named the property Stonyfell, after the slopes in England called 'fells'. Here he planted the original Stonyfell vineyard. The principal part of the vineyard was planted in 1860, with 20 acres of Black Portugal grapes, and two and a half acres of muscatels.

In 1880 the quarry was worked by hand-mining methods. Secondary breaking of the stone was also done by hand with spalling hammers. In 1881, Henry Dunstan, who by that time owned both the quarry and the vineyard, installed a steam-driven Hope Stone Breaker, and for the first time steam was used in South Australia for crushing stone. This would have gone some way to help meet local demand for metal screenings - aggregate used as a base in tar paving (for council footpaths), roads and concreting. The establishment of the Dunstan Tar Paving and Road Metal Depot at Kensington Park was equally innovative and timely, being ideally placed for servicing the roads of Adelaide, particularly the eastern suburbs.

It was envisaged that the Hope Stone Breaker would relieve some of the burden of breaking all the stone by hand. However, it did not relieve the men's workload. Production increased with the aid of the crusher, but no one escaped the noise, the continuous knapping (breaking up) of the larger stones, the loading by hand or the dust, heat and rain. These were long days. The men would rise early, don their work clothes and boots (with metal protective plates), and set forth on foot with lunch bags from their small houses in the surrounding suburbs of Leabrook, Kensington Park and Magill. They would arrive at the Dunstan sheds and stables, harness the draught horses to wagons and move up to begin their day at the ochre rock face.

Quarrying was a dangerous business. A young Canadian, Thomas Keays, who later became an overseer at the quarry, wrote in a letter to his family in 1886: 'Having just got over the Colonial Eye Blight, I received a blow with a stone from the crusher'. In a letter a few months later, he mentions having passed the St John's Ambulance test, valuable knowledge to have in his line of work. Keays also complained of asthma symptoms which later claimed his life. Silicosis is a well-recognised disease resulting from exposure to dusts containing silica or quartz. Modern methods of dust control and employee protection have reduced exposure to such an extent that occurrence of this disease is now rare.

Don Harris, whose father worked at Stonyfell, remembers visiting the quarry with his family and friends in a horse and cart in the 1910s. The greatest excitement of all was to be sped up the quarry slope in one of the empty trolleys as another one, fully laden with stones, came hurtling toward him, passing at a spur halfway, and then continuing down to the giant steel jaws of the crusher below.

In 1939, Stonyfell Quarry amalgamated with the other Adelaide Hills quarries to become part of Quarry Industries. Stonyfell vineyard was sold to Penfolds Wines which still operates the vineyard today.

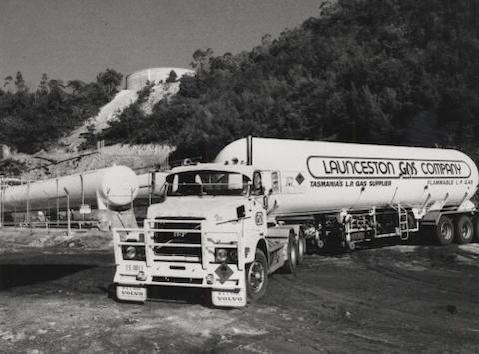

Launceston Gas Company

In 1980, Boral bought its second New South Wales brickworks, Pacific Bricks at Badgerys Creek, west of Sydney. It also made a far less publicised acquisition in 1981, taking over Launceston Gas Company for $2.35 million.

History of Launceston Gas Company

In 1860, Launceston's first gas manufacturing plant was built. This consisted of a horizontal retort house. Retorts were made of clay or metal and set in large arched ovens. They were heated with coke until they became red hot. Coal was taken from an adjoining store and placed in the retort by hand. When it was full, the mouth of the retort was closed with an iron plate.

The gas rose from the coal and ascended a series of pipes, until it reached the hydraulic main where it bubbled up through water, leaving the retort house full of impurities and very hot. From the retort house it passed through a 'scrubber', which had a revolving water apparatus inside. This attracted a large portion of the tar and commercial liquor that needed to be removed.

From this apparatus, the gas then passed on until it reached the condensers which cooled the gas to 45° Fahrenheit (7.22° Celsius). It was then passed through purifiers where the carbonic acid, sulphurated hydrogen, ammonia and other impurities were extracted. By this stage it was usable and held in a gas container to be drawn off as required.

In those days, gas manufacture involved hand stokers placing coal on beds using long shovels. After twelve hours they would then extract the coke left after the gas had been carbonised from the coal. This was a very dirty labour-intensive job, one that would certainly not satisfy modern occupational health standards.

The gas was then pumped into a small container in the south-east corner of the gasworks by a steam exhauster and piped into the Launceston gas distribution system. This method of gas manufacture was used until the 1930s, with most of the coal coming from Newcastle in New South Wales.

In 1931-32, a vertical retort house was constructed by Launceston Gas for two reasons. Firstly, the original retort house was so outmoded that it was becoming uneconomical and secondly, the Launceston gas distribution network had grown so much that the plant could not keep up with demand.

The vertical retort house consisted of eight retorts and was about 120 feet high. A conveyer belt took the coal to the top where it was stored in bunkers. Every hour coal was released from the bunkers into the retorts, a continuous carbonising process that took about twelve hours. Only one stoker was needed; his job was to remove a portion of the residual coke from the bottom of the retort. The coal was slowly fed from the top to the bottom of the retort continuously over the twelve-hour period.

Using this method of production, the quality of the gas could be changed by the rate at which the coke was extracted from the bottom of the retorts. The quality of the coke was also very high and the gasworks had quite a profitable sideline selling to the various blacksmith shops throughout Launceston.

By 1950, four gas containers had been constructed, one of which held 250,000 cubic feet of gas - the equivalent of two days' supply for Launceston. In 1956, a carburetted water gas plant was built. This was a Humphries and Glasgow plant using coal extracted from a local Tasmanian coalmine at Fingal. The quality of this coal was poor, and naphtha gas was added to enrich Launceston's town gas.

In 1977, both the vertical retort house and the Humphries and Glasgow plant were replaced with a catalytic reforming plant, which used LPG butane as fuel. This method of supplying town gas is still used today, though it is likely to be phased out in the not-too-distant future.

Computers and Acquisitions

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Boral had established itself as a major player in the building and construction materials industries. This was due in part to one of Neal's first moves on becoming chief executive. Ian Potter, who had advised Griffin in the company's early years, was still on Boral's board but Neal employed Brian Saunders, who had been a management consultant with Coopers & Lybrand, to come in full-time as corporate planner. This role was directly related to acquisitions and he worked directly for Neal.

Saunders used a computer modelling program called the International Financial Planning System (IFPS), to assess the effects of acquisitions. Boral was among the first Australian companies to use this kind of modelling. Using this system, they could put in all the variables: how much Boral paid; how much Boral should offer in shares or cash, as well as making projections - for example, the likely outcome if the profits did not meet budget. A major complication for Boral when it acquired companies was that Caltex still had an interest in the company. This meant that Caltex had the right to participate in any share issue. If Boral offered shares to shareholders in the company it was taking over, it had to issue extra shares to Caltex.

An extensive article in the now defunct Australian Business Magazine of October 1981 profiled the company, by that time Australia's twentieth largest. The magazine quoted Neal's criterion as simply: earnings, not assets. The following excerpt gives an insight into how Boral's operations were perceived by the financial press at that time.

Boral's tough task master

For a company the size and power of Boral Ltd, it seems odd that the only evidence of the Computer Age at its North Sydney headquarters is a single terminal. But this innocuous looking business aid is, in fact, chief executive Eric Neal's secret weapon in elevating Boral to among the top ten within the next few years. The terminal, linked via Control Data to a computer bank in Melbourne for security reasons, contains the inner financial details of the 100-odd companies Boral has selected as potential takeover targets - a corporate shopping list that includes some big names.

Indeed, if yours is a company with a strategic interest in building materials, resources or a similar growth area, then chances are Boral is eyeing your property. The terminal, employing a sophisticated program known as Interactive Financial Planning system, which provides not only key financial ratios within half-a-second but also the effects on Boral of any changes in those ratios, was introduced by Eric Neal in 1975 to handle the takeover of Cyclone Company of Australia, the steel products maker.

And it has been the selector of the most suitable targets ever since, including the acquisition of Australian Gypsum Industries, Quarry Industries, Pacific Brick, and the group's push into the US roofing tiles and bricks market.

If the computer says 'go', Boral moves - its usage remains a well-kept secret. Only two executives know how to operate the terminal, using a passcode which changes every two months. Boral's five chief general managers - the next line of management below Neal - are called in to contribute, but they are given access to only part of Boral's knowledge of the bid.

BMI Acquisition

BMI had first come to Boral's attention in the 1970s. The company operated quarries in New South Wales in its own right and owned 50 per cent of Ready Mixed Concrete (RMC) which operated Australia-wide with CSR. The agreement between BMI and CSR was restrictive to BMI. Under the contract BMI could have concrete and quarrying operations only in New South Wales. Boral was not interested in taking over BMI with this condition attached. In 1981 BMI and CSR decided to split RMC. BMI took assets which gave them operations in Queensland, Victoria and Tasmania as well as in the United Kingdom and Indonesia; CSR took the remaining RMC operations.

As a result, BMI became a large operating company, but it made some bad business decisions. Before superannuation was common to the whole of the Australian workforce, BMI introduced a superannuation scheme from shop floor to board level. All BMI employees were members, from directors, right through management to blue-collar workers. The company's contribution was 11 per cent of wages, with no contribution from the individuals. At the time an 11 per cent surcharge on wages was then enough to make most businesses uncompetitive, and BMI became just that. The superannuation scheme adversely affected the company's profits. Neal said, 'They were paying more than they could afford in superannuation - particularly blue-collar superannuation - at a time when their competitors either didn't have it at all, or it was on a much more modest scale.'

At about the same time, Boral had introduced a scheme - the Boral Gas Provident Fund - which it extended to all workers throughout the Boral Group. A worker who elected to join agreed to pay from 1 to 4 per cent of his or her salary into the fund and this amount was matched by the relevant Boral subsidiary company. It was an accumulation fund, so the maximum cost to Boral was 4 per cent for each employee. Under the scheme, if workers resigned before retirement they forfeited the company's contribution, though they received their personal contributions over their period of employment. About 70 per cent of the Group's employees joined the scheme when it was introduced.

The company's computer division was also centralised by Neal under David Pennells, who was appointed Boral's first manager, computer services in March 1976. Apart from the 'takeover terminal' the company's computers - two Burroughs main frames - are located where much of Boral's work is, Melbourne and Brisbane.

The article also speculated on Boral's next move in terms of acquisitions. The companies mooted were ACI, BMI and Pioneer Concrete. John Alexander, the journalist who wrote the article, surmised that ACI was probably too big, BMI might not fit Boral's strict criteria and Pioneer Concrete might be a problem because relations between Neal and Antico, in Alexander's words, 'were not close'. Boral's next acquisition turned out to be BMI in 1982.

Once BMI and CSR carved up RMC, Boral's interest was rekindled. BMI was at this stage a company of about the same size and asset value as Boral. For many years, CSR had a large BMI shareholding, which they had agreed not to sell without notifying that company first, so Boral began acquiring shares independently on the stock market. During the takeover, in October 1982, Caltex issued a press statement which advised it was selling its 11 per cent shareholding in Boral to fifteen institutional investors. It said in part:

Directors of Caltex said the company had enjoyed a long-standing relationship with Boral and had been very satisfied with its investment. The decision to sell was in line with the Company's policy to rationalise its activities and interests. In taking the decision to sell, the Board had in no way been influenced by Boral's current takeover of BMI Limited, nor did it lack confidence in any way in the continuation of Boral's highly successful performance.

The takeover of BMI was very significant for Boral's growth and future development. As a result, Boral attained the leading market position in building and construction materials, and strengthened its operations in other states. BMI also gave Boral bases in the United Kingdom and Indonesia.

BMI History

In 1883, Sterring and Partners opened a gravel pit on a bend in the Nepean river near Emu Plains in Sydney's far west. Sydney was experiencing a building boom and the colony's growth meant opportunities for enterprising individuals. New roads were being constructed and existing dray tracks needed upgrading as the early settlers spread out from Farm Cove across the plains to Parramatta and beyond.

In 1903 The Emu and Prospect Road Gravel and Metal Company was formed. This company had been through a number of name changes and had already purchased Sterring's gravel pit in 1885. This name change reflected the company's purchase of nearby Prospect Hill, where hard rock had been quarried since the colony was first established.

In 1919, the Prospect quarry was subsequently acquired by New South Wales Blue Metal Company. A new company was then incorporated in 1921, the forerunner of BMI, named New South Wales Associated Blue Metal Quarries Limited. The company took over the operations at Prospect as well as quarries at Minnamurra and Bombo on the south coast of New South Wales. These south coast purchases also provided a transport vessel, the SS Dunmore.

The New South Wales south coast was particularly rich in high-quality basalt, and deposits around Kiama had been quarried since the mid-1800s. Shipping was the only practical method of moving quarry products from Kiama to the Sydney market, and this method of transport has been used periodically up to the present day.

In 1935, due to the Great Depression, the New South Wales government, which also had quarrying operations at Kiama and Bombo, decided to sell. The deal included a ship, the SS Bombo, to transport the basalt to Sydney. Money was tight and no single company could afford to purchase the state government's operations. A joint venture company known as Quarries Pty Limited was formed. This saw the amalgamation of many of the small hard rock quarries and river gravel deposit operators on the south coast of New South Wales and the Sydney metropolitan area. Shares in this venture cost ninepence; the new partners did not have the liquidity to buy them outright. The Bank of New South Wales (now Westpac) provided the shortfall of funds for the purchase, after obtaining the appropriate guarantees from each participant.

Blue Metal and Gravel Limited (BMG) was a marketing company formed in 1935 to sell the aggregate for Quarries Pty Ltd. (The New South Wales Companies Office must have been confused by the quarrying industry's use of the words 'Blue Metal', since so many early quarrying companies included them in their names.)

During the Depression and World War II, BMG gradually closed down most of its smaller south coast quarries. The company decided to concentrate on developing the first-class basalt at its Dunmore quarry and the Prospect quarry at Greystanes in Sydney's west. Boral continues to operate both quarries.

SS Bombo Tragedy

For many years the SS Bombo transported blue metal aggregate in 600-ton loads from Kiama harbour to Blackwattle Bay in Sydney. In 1940 both the SS Dunmore and SS Bombo were commandeered by the Royal Australian Navy for service off Australia's northern coastline. There is no record of the fate of the SS Dunmore, but the SS Bombo was returned to BMG in July 1947 and, after a complete refit, resumed the Kiama-to-Sydney blue metal run.

During a severe south-easterly storm in 1949, the Bombo foundered at night off Wollongong while trying to take shelter in Port Kembla harbour. The ship was in excellent condition, but the load of 3/4-inch aggregate, in the partly filled forward hold, shifted in the big seas. The movement of the cargo was so rapid that there was no time to send out a distress call. The Bombo rolled over and sank within minutes; the crew had no time even to launch the lifeboats. The first alert of the ship sinking came when the survivors made it ashore the following morning. The captain and eleven of the fourteen crew died in the tragedy.

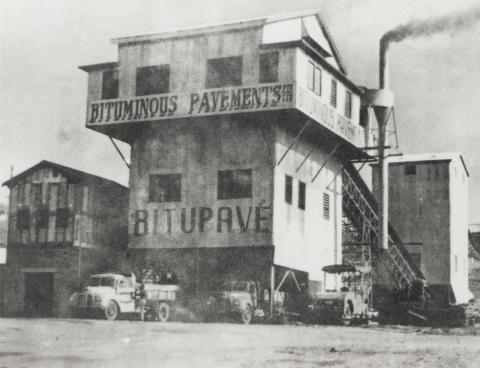

In 1951, BMG began a program of diversification, which saw the formation of three subsidiary companies: Howard Engineering to establish a repair and maintenance depot for company plants; Bituminous Pavements to operate a hot mix bitumen plant at Prospect and to contract for the laying of asphalt; and Mobile Plant to operate road vehicles for transporting quarry and other products. In 1952, Blue Metal Industries was registered as a holding company for these expanding interests. However, the reorganisation of the company's capital structure was not finalised until 1954 because of the generally unstable economic environment. Not until 1978 was the name officially changed to BMI Limited.

Prospect Hill

Prospect Hill, the site of the BMI Quarry, was the highest point between Sydney and the Blue Mountains, and in the early days of the colony was used as a navigational landmark. In April 1788, Captain Arthur Phillip and his party came to Parramatta and five days later ascended a small hill with extensive views of the surrounding area. Phillip named it 'Bellevue', which was translated as 'fine prospect', from this the general area became known as Prospect.

Many people are under the misconception that quarrying of blue metal (a term used in the early days of the colony, when settlers used any hard rock in the Sydney region for the simple roads that were made) on Prospect Hill began with the construction of the wall and aqueducts for Prospect reservoir. Historical records show that quarrying took place on the intrusion long before this and, as early as the 1820s, local roads were partly paved with broken grey dolerite from the surface of Prospect Hill.

In 1832, Charles Darwin, the English naturalist and geologist famous for writing Origin of the Species, visited Prospect Hill to observe the dolerite. Darwin mentioned it in his book, The Voyage of the Beagle.

William Lawson, the explorer, acquired a grant of some five hundred acres including Prospect Hill, in 1808. In 1846, his third son Nelson built an extensive house there which he called Greystanes House. Prospect dolerite has a tendency to weather to a grey colour and Lawson, who was of Scottish origin, called stone `stane', hence the name Greystanes. This in turn provided a name for the adjacent suburb when it was established.

During the 1880s, hundreds of workers came to build the new reservoir at Prospect, to provide clean, plentiful water to the growing population of Sydney. The colony's water supply had been inadequate since the 1850s. The water situation eventually became so serious that Sydneysiders were forced to queue day and night at local fountains to replenish their water supply.

Industrial development in the colony was also hampered because of the general water shortage.

Greystanes House was set on the slopes of Prospect Hill, overlooking the surrounding farms and grazing lands. This magnificent home was finally demolished in 1946 after falling into disrepair. The area where it stood has been partially quarried, though the Moreton Bay fig tree that stood beside it remains and has a conservation order on it. During World War II the US Army established a camp on part of the Greystanes estate. It is understood that this contributed to the degeneration of the building, which was demolished by order in 1946. Some of the original bricks from the house and iron-work from the driveway have been incorporated in the front entry of Greystanes High School. The Boral Resources main gate on Greystanes Road has been moved slightly to the south to preserve intact the original entrance to Greystanes House.

Gold on Prospect Hill - Hooper's Folly

One afternoon in 1961, Ron Parrot, Prospect Quarry's manager, was sitting quietly in his office at Greystanes. Bob Hooper, Prospect Quarry's foreman, suddenly burst in unannounced to tell him that gold had been discovered on Prospect Hill. Parrot said that he found that hard to believe, but Hooper was insistent. Furthermore, Hooper assured Parrot, unless he agreed immediately to the whole of Prospect Hill being pegged out with gold leases, the company could expect an influx of hundreds of gold prospectors, all staking their claims on Prospect Hill - something like the gold rushes of the 1850s and 1860s.

Hooper was a mining engineer by trade who had previously worked in Western Australia in the goldmining industry. With this in mind, Parrot reluctantly agreed to the expenditure of quite a large sum of money to take out some gold mining leases - which had to be purchased in 25-acre lots. The quarrymen pegged out BMI's Prospect Hill quarry, and then convinced themselves that the gold-bearing vein was running in the direction of Styles Blue Metal Quarry, an adjoining business. Caught in gold fever, and in the middle of the night, they climbed over the fence and pegged out Styles Quarry as well.

When Hooper staked out Styles Quarry, all hell broke loose between RMC and BMI. Sam Stirling, RMC's managing director, had secretly been negotiating to buy Styles Blue Metal and Stirling interpreted the staking out of the quarry as a deliberate attempt to prevent the sale going through. After tempers cooled, the whole matter was explained and Stirling acquired Styles Quarry for RMC.

Secure in the knowledge that they had the gold deposit claimed, Hooper set about taking an ore assay sample to confirm their find. The first sample indicated that there was indeed gold in payable quantities in Prospect Hill. However, to be sure, a second assay sample was taken which was negative, effectively quashing the potential millionaires' hopes. The site where the `gold' was discovered was a heavily mineralised shear zone, which became known as 'Hooper's Folly'.

When Boral acquired BMI, it immediately found itself in the timber business. It now owned Allen Taylor and Co. Limited which had been taken over by BMI in 1970. Brian Saunders remembers: `Boral had a fairly open view to whether or not to keep the timber business when they took over BMI. Obviously it wasn't able to slot in as easily to the scheme of things as quarrying, for example.'

His department was given the task of researching the timber industry. At the time, there was some speculation that timber softwood supplies would exceed worldwide demand in the next decade. This prediction was based on the fact that North America had abundant softwood supplies. Saunders recalls, 'What happened was that the environmental groups there [in the United States] through extensive government lobbying, cut off the supply'.

In the late 1970s, BMI realised that a huge resource was being wasted in the form of sawmill residue or woodchips. These could be used to create pulp for paper production, during which wood must be broken down to a pliable yet strong form. Chipping wood into pieces roughly the size of a fifty-cent piece is the first stage in this process.

Sawmillers Exports was incorporated in a joint venture between BMI and two Japanese companies to export woodchips to that country. In 1978 the Federal and New South Wales governments approved the proposal and the first shipment of woodchips was made in 1981.

Timber, woodchipping in particular, was a controversial area for Boral. The conservation movement had been pressuring governments to abandon it since the 1970s. Finally, in 1982, after a decade of debate and intense lobbying by environmentalists, New South Wales Labor Premier Neville Wran, produced the 'Rainforest Decision'. This resulted in a period of turmoil for the timber industry, which saw a general decrease in quotas and volumes. Instead of arguing Boral's case to get government agreement, Eric Neal accepted the principle of sustained yields, value-adding and the general rationalisation of Boral's timber interests. The company closed or sold five sawmills south of Nowra on the New South Wales south coast and closed a number of small north coast mills as well. Boral also undertook wood sale agreements and accepted responsibility for maintaining regional employment in areas where the company operated.

Allen Taylor History

Allen Taylor was born in Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, in 1864. He started work at the age of ten as a 'nipper and messenger' for a railway contractor. Later he worked twelve hours a day as a railway construction labourer on several lines, including the south coast of New South Wales. Taylor eventually became a contractor in his own right and, having saved some money, decided to move to Sydney to attend night school and improve his education.

He became a timber and shipping agent early in 1892, running his business from his home in the Sydney suburb of Annandale until 1895. By that time the business had grown enough for him to open an office at Union Street, Pyrmont.

Interested in local government from an early age, Taylor became an alderman with Annandale Council in 1894. In 1902 he was elected to the Sydney City Council as the alderman for Pyrmont Ward. He served continuously for ten years and as Lord Mayor of Sydney for six years and was knighted for his contribution to civic affairs in 1911. Taylor Square was named in his honour, and he is credited with bringing many improvements to the Sydney metropolitan area.

The early success of the timber business was attributable to Taylor's talents as a salesman and administrator. He would canvass all the timber merchants around Sydney, soliciting orders and asking for specifications. Then he would place orders with north and south coast sawmills, making clear when they required delivery. As soon as Taylor found out when the order would be ready, he arranged for its prompt shipment to Sydney. By insisting that his instructions to sawmills and shipping agents were carried out to the letter, Taylor's reputation for reliability grew rapidly, and so did the business.

In February 1905 the firm was incorporated as a public company - Allen Taylor and Company Limited - the seven original shareholders all being members of the Taylor family or employees of the company. The following year shares were taken up by members of the public. In 1907 the company bought the first of its sawmills at Nambucca on the north coast of New South Wales, adding a second at Port Stephens, north of Newcastle, in 1909.

The company won valuable contracts to supply the Public Works Department with sawn hardwood in 1913. The following year, the company successfully tendered to supply sawn hardwood, tallow wood, blackbutt, hewn ironbark and wood paving blocks to the New South Wales railways for the Sydney area. The business continued to flourish into the 1920s. Charges of collusion between Allen Taylor and the Railways Department (brought by persons described by the company as 'disgruntled tenderers') led to a Commission of Enquiry appointed by New South Wales Premier Jack Lang. As the company records succinctly said, 'Nothing came out of the commission'. One of the more interesting contracts the company won during that controversial time was to supply a vast quantity of timber for decking and sleepers for the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

By 1930, the start of the Great Depression, business was described in a report to the board of directors as 'very dull', and the following year the situation became serious. One debtor after another went into liquidation, business was painfully slow and prices uneconomically low. Drastic measures were taken, salaries and directors' fees were slashed and some assets were sold, belt-tightening that helped the company survive. It was not until 1935 that business began to improve; as late as 1938 it was reported that 'money is very hard to collect'.

Taylor, who had indicated he would like to retire on several occasions, had always been persuaded to remain chairman of the company (though he relinquished the position of managing director), died suddenly on 30 September 1940. World War II had brought the company back into full production, with timber being supplied to the Department of Defence as well as Allen Taylor's regular clientele. Expansion continued during the war years, despite stringent government controls and manpower shortages.

By 1970 Allen Taylor's sawmills and associated contractors to the company were flourishing throughout New South Wales. In that year BMI took over the business.

Allen Taylor specialised in hardwood sawmilling and BMI's management believed there were long-term advantages in the softwood market. In 1978, BMI acquired Timber Industries Limited which was based in Oberon, New South Wales, and had recently converted its hardwood mill to softwood.

The Story of Timber Industries Limited

In 1926 Hugh Cotton went into business as an agent dealing in timber mining supplies on the Broken Hill minefields. At the time 95 per cent of the timber used in the mines was Oregon, imported from America. Only the mine shaft and ore chute linings were made of Australian timber. Cotton could not understand why New South Wales hardwoods were not used, and in 1936 he was given permission to test their use in the mines. He contracted with East Coast Mills and was appointed the agent for Heron's Creek Timber Mills Pty Ltd at Port Macquarie.

In 1931 Bob Cotton (later Sir Robert Cotton, Federal Government Minister and Australian Ambassador to the United States) went into part¬nership with his father, trading as HLC Cotton and Son. They expanded the business, supplying the North Mine Limited at Broken Hill. The mill at Heron's Creek was not large enough to supply the needs of the three mines at Broken Hill and when World War II began in September 1939 imports of oregon were curtailed and by 1942 there was a timber supply crisis.

With money borrowed from North Broken Hill, Cotton and his father bought a sawmill licence from an Oberon partnership, Cunynghame and Starr, who had a hardwood mill on the Jenolan Caves Road. In 1943 Timber Industries was formed near the town of Oberon and the first log cutters and haulers were hired to supply the mill. Later the same year the mill started production. Together with Heron's Creek Mill, Koopers Mill at Batlow, and later WJ Machines Mill at Wingham, Timber Industries supplied the Broken Hill mines for the rest of the war. These operations were so successful that at war's end importing American timber was not resumed.

In the 1950s the Cottons realised that the New South Wales hardwood supply was finite and the Oberon mill was upgraded to cut both softwood (radiata pine) and hardwood. After a while softwood milling began to take over. By 1978, the last hardwood log had been milled and BMI bought Timber Industries from the Cotton family.

Timber Industries installed Australia's first machine stress grader in a production line. This provided a mechanical means of testing the strength and flexibility of the wood under load. Before this, timber graders were used to visually assess the wood, using the knots in the planks as the main indicator of the woods' strength. The machine stress grader was invented by the Forestry Commission of New South Wales Division of Wood Technology. Using this innovation, in conjunction with a prefabricated roof truss production line to make roof frameworks, Timber Industries was the first company to market radiata pine roof trusses in New South Wales. The Housing Commission became one of the company's biggest customers. When BMI bought Timber Industries in 1978 the business underwent a period of rationalisation and improvement and the sawmill's capacity was increased to produce 130,000 cubic metres of softwood logs per annum. By July 1995 the roof truss business had been phased out. It was no longer a major part of the company's operation and Boral increasingly found itself in direct competition with its customers in this division.

Oil Company of Australia

Even in its early days, Boral had been involved in Australian oil and resource exploration, usually in joint ventures. In 1982 management decided to increase its activities in this area and bought 18 per cent of Oil Company of Australia Limited (OCA).

This company had been incorporated in 1978 and floated in 1979 to develop exploration permits in the Canning Basin in Western Australia and the Denison Trough in Queensland. The first success came in 1981 in the Jackson oil field in the Naccowlah block and the Merivale gas field in the Denison Trough.

Over time Boral increased its holding to 40 per cent and in 1985, after making an offer for the remaining shares, became the principal shareholder with 85 per cent. In 1990 the company began selling natural gas from the Denison Trough to Queensland Alumina Limited in Gladstone under a ten-year contract. OCA substantially increased its reserves in the Surat Basin with the acquisition in 1990 of Hartogen Energy Ltd. The company operates mainly in Queensland and is one of the largest onshore oil and gas exploration operators in Australia.

Strong Financial Controls - Boral's Management Philosophy

In the early 1980s, Boral had a very simple, small and select management team. Only fifty people worked in its head office and corporate planning was confined to an elite group. Business Review Weekly likened the Boral team to one 'coming straight out of the management textbooks'. The company's motto was 'In search of excellence', and Neal said in the interview that the company was always re-examining its business management tasks, techniques and goals.

It was a very different company to the Boral that operated in the late 1960s. At a highly publicised annual meeting at that time, Boral management had been roundly criticised by shareholders for 'profitless prosperity' - during a period when the company was renowned for dramatic and profitable takeover raids - the benefits of which did not flow to the bottom line.

The company philosophy under Neal was to grow and enhance the earnings per share. Neal said, 'What I was trying to do was always look at the best way to improve the earnings per share. People invest in a stock because they want a better return than they can get from a bank or a building society. So, without doubt, the objective of the company was to make a profit. We placed an enormous emphasis on cash flow. But at the same time we recognised that by doing so, we also had very strong obligations to our employees, the community and the environment.'

In the eight years since he took over control of the company Neal had added some $400 million worth of new businesses to the Boral Group. All acquisitions were funded from internal resources or by means of Boral shares. Boral management never believed in high borrowings, so they could take advantage of opportunities as they arose.

Peter Finley who was chairman at the time said, 'We had a very direct management at Boral. Even though the operations were very decentralised, profit was looked at right down to the smallest areas. Each division set its own targets, submitted them to head office and then tried to meet them. So everyone in the organisation was aware and was fully conversant with the company's goals. If a division had difficulty in meeting a realistic budget, then it would be given every assistance by head office and Neal himself. We wanted to encourage divisions to be autonomous, but if they got into trouble then it was senior management's job to help.'

The speed at which Boral was able to change the fortunes of its new acquisitions was partly due to its standard accounting, financial controls and reporting systems. Once a company entered the Group, it had to adopt Boral's systems. This made it very simple for management to pinpoint any problem areas and see exactly where each division stood.

Industrial Relations

Most of Boral's operations in the early 1980s employed between twenty and one hundred staff. As a result they did not have the same problems encountered by other manufacturing and mining companies, which had to deal with workforces of between three hundred and one thousand employees per plant.

Being involved in areas like quarrying, pre-mixed concrete, sawmilling and steel also meant that safety issues were very important. The Boral Group therefore appointed a group medical officer attached to the corporate staff to handle occupational health and safety. Each state division also had a part-time safety officer and a loss control officer, whose job it was to audit each division's safety record, assist management in the various plants and achieve the highest possible safety standards. Monthly reports on accidents were seen by all members of the Group's board of directors. Where ten or more people were employed, Boral introduced occupational health and safety committees. This program was very successful, resulting in a 42 per cent reduction in the frequency rate of lost time injuries.

Communication was the first priority in Boral's industrial relations philosophy. Neal said, 'I believe that if people talk together then many problems can be solved before they occur. We had a preventative approach to industrial problems.' The company did not have a formal industrial relations structure or department. Line management was expected to handle employee relations and each manager was directly accountable. Neal said, `What our line managers may have lacked in sophistication and training, I believe, was made up in their awareness, their closeness to the situation, and their genuine desire to do the right thing. In corporate head office, we believed that problems should be settled on the shop floor, and we placed extreme emphasis on developing good relations between management and labour.'

During 1982 general industrial disputes, connected with wage claims and campaigns for a thirty-five hour week, affected the profitability of many Boral operations. In 1983, every Boral division concerned with home construction experienced a downturn in sales. Home dwelling construction approvals were at their lowest level since 1965-66, dropping 26 per cent from their 1980-81 peak. Cyclone products were also affected by the worst drought in Australia's recorded history. There were some reductions in employment, but despite this there was widespread support in most areas of the company for the wage pause.

In 1985 Boral purchased City Bricks which had been operating from Scoresby in outer Melbourne since 1963. Pictured above is the company's original brickworks in Camberwell Road, Hawthorn, in 1923.

City Bricks' brickworks in the Melbourne suburb of Malvern (above). Its neighbouring Tooronga Quarry (below) was closed in 1983.

Employee Share Scheme

In November 1983, for the first time, Boral gave staff the opportunity to become shareholders in the company through an employee share scheme. As a result of this, 28 per cent of Boral's workforce became shareholders in the group. By 1984, there were over 12,000 Boral employees worldwide, and Boral was in the top fifteen Australian companies. That year Business Review Weekly rated Boral the third best managed company in Australia, and placed it fourth as the best long-term investment stock.

By 1985 the state of home building and general construction activity in Australia had totally turned around, partly due to Neal's initiative in lobbying the Hawke government and organising a national housing summit at Parliament House in Canberra. This resulted in the First Homeowner's Scheme, a government assistance program for young home buyers. This scheme, coupled with the Bicentennial Roads program in preparation for Australia's two hundredth birthday, greatly improved Boral's outlook.

Johns Perry Limited

By 1986, Boral's fortieth anniversary, the company had 17,000 employees worldwide and 51,000 shareholders. In February of that year, Boral expanded its involvement in the manufacturing and engineering industries with the acquisition of Johns Perry Limited. This company resulted from the 1966 merger of Johns and Waygood Company, a Melbourne-based lift manufacturing and engineering company, and Perry Engineering, one of Adelaide's oldest established engineering companies. At the end of 1985 Peter Yunghams, a Melbourne lawyer turned corporate raider, had received some publicity about his growing shareholding in Johns Perry. The company had a very profitable lift division and was also involved in some areas of manufacturing that complemented Cyclone's steel, tube and wire products for the rural sector in the form of springs, strapping and rope. Johns Perry also had a general engineering division and some foundries, but the company's profitability was less than it could have been.

One Monday morning in November 1985, Eric Neal telephoned Don Laidlaw with whom he had negotiated the Quarry Industries acquisition; Laidlaw had retired as an executive with Johns Perry at the end of 1973 but retained his position on the board. Neal was calling from Launceston where he was attending a board meeting of Launceston Gas Company. On his arrival in Tasmania, he picked up a hire car to drive up to Launceston. On the road up, he drove past Johns Perry's new factory at Breadalbane.

With time to kill on a Sunday afternoon, Neal had driven around the back of the factory, found a gate open and taken himself on a 'Cook's tour' of the business. He rang Laidlaw to ask him who was buying Johns Perry shares and Laidlaw told him about Yunghams. Neal said, 'Well, we have a list of about fifty companies that we are interested in, Johns Perry is not one of them, but you've told me in the past that the lift business is good. I'm going to be down here (in Launceston) for a couple of days, I'll organise for someone in Sydney to come down with some Johns Perry annual accounts for me to read.'

When Neal returned to Sydney he talked to Johns Perry's chairman Bob Millar as well as two other directors. Boral acquired about 20 per cent of Johns Perry from institutional investors and Yunghams, and then made a takeover bid offering Johns Perry shareholders $5 a share, or five Boral shares for every three Johns Perry shares. The Boral share price rose and the offer was worth $5.60 to Johns Perry shareholders. Rumours circulated about counter bids, but none eventuated and the takeover went through rapidly.

The History of Perry Engineering

Perry Engineering started in 1897 when Samuel Perry, a blacksmith from Shropshire, came to Adelaide and started a foundry and forge. He died in 1930, leaving the business to his nephew, Frank Perry, on one condition: if the business made a loss in any one year, it was to be closed and sold. To his credit, the younger Perry managed to keep the company going through the Depression and World War II. In 1947, Perry decided to make it a public company, as they were doing a considerable amount of contract work for the mines at Broken Hill. The underwriter of the share issue, E.L. & C. Ballieu, arranged for North Broken Hill, Broken Hill South and Zinc Corporation each to take a 10 per cent interest in Perry Engineering, while the family retained slightly over 50 per cent.

Don Laidlaw joined Perry Engineering in 1956, and was involved in changing the nature of the business. He said, 'We went back into structural steelwork for buildings. At that stage the South Australian economy was buoyant, and we started to make mechanical presses for the car industry.' General Motors, Ford and Chrysler had all decided to build large steel press shops there. During the next eight years, the company manufactured about four hundred mechanical presses for automotive and general industry. Laidlaw says, 'This became a bread-and-butter line.'

In 1965 Sir Thomas Playford, who had been the Liberal Premier of South Australia for twenty-nine years, was voted out of office. At the same time, the expansion of the car industry tapered off, BHP completed its steelworks at Whyalla and the Torrens Island power station had been completed. Ten years of boom in South Australia came to an end. In 1966 Perry Engineering merged with the Melbourne-based engineering and lift company, Johns and Waygood, which had been operating since the 1860s. The company was called Johns and Waygood Perry Engineering and did not change its name to Johns Perry until 1976.

Blue Circle Southern Cement

In the early 1980s, Boral had the sand and aggregates but did not have its own cement supply, an important component of concrete, as did other major construction companies. Boral was at a significant disadvantage if it did not control its own cement production because major competitors with their own cement could afford to drop their prices below Boral's. Cement was the key to Boral's future in the concrete and quarrying business.

Boral had been watching Blue Circle Southern Cement for seven years. The company had been established in 1974 with the merger of Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers - the Australian subsidiary of a UK company - and Southern Portland Cement, which was owned by BHP. Blue Circle Southern Cement, was a partnership between the two. BHP owned 42 per cent, the same as the English company Blue Circle Cement PLC. Boral's management felt that a cement company wasn't BHP's area of interest and that the English company probably did not consider it a long-term proposition. From 1980, Neal maintained contact with Brian Loton of BHP and Sir John Milne, the managing director of Blue Circle Cement PLC. Both Brian Loton and John Milne had politely acknowledged Boral's advances, said they had no present intention of selling, but noted Boral's interest. Nevertheless, Neal maintained contact with both, calling on Milne each time he went to England and meeting with, or telephoning, Loton at least once a year to touch base.

In 1987, Neal finally received a call from BHP to say that they had decided to invite bids for their shareholding in Blue Circle. It was clear to him that if they were inviting bids for a 42 per cent share in a company, the best course was to make a takeover bid for all the shareholders. Boral offered them $5 a share, which was below market price. Neal recalls, 'The day before our offer ran out, Geoffrey Heeley from BHP and a Blue Circle Cement representative came to my office in Sydney and we agreed on a slightly higher price, on the basis that if we increased the offer both BHP and Blue Circle Cement would sell.' Boral increased the offer and moved from a few per cent to 85 per cent that afternoon.

This move into cement took Boral into a different world and the company culture changed. Bruce Kean who succeeded Neal as Boral's chief executive in 1987 recalls, 'Boral's resource managers had always seen cement as the devil, and all of a sudden this devil was inside their camp. The internal friction it created was unbelievable because Boral was now selling cement to independent distributors. Up until the takeover of Blue Circle Southern Cement, Boral had been able to introduce its name into most of its acquisitions quite easily. But to offer Boral concrete as well as Boral cement, and to have green and gold trucks entering competitors' yards, was virtually unthinkable.' Blue Circle, although it is now part of Boral, operates under its own name. Jim Layt, Blue Circle's managing director before the takeover, stayed on to manage the company for Boral after the acquisition.

The History of Blue Circle Southern Cement

Southern Portland Cement Limited had been incorporated in 1927 by Hoskins Iron and Steel Company Limited. This new wholly owned subsidiary mined limestone at Marulan in New South Wales for the parent company's Port Kembla steelworks. However, not all the limestone excavated was suitable for steel production, and it was decided to use this excess material to manufacture cement. A plant was erected at Berrima, close to the coal and shale deposits required for cement production.

In 1928, Hoskins Iron and Steel formed a new company, Australian Iron and Steel, to acquire the undertakings of Hoskins Iron and Steel and its subsidiaries, as well as an associated structural engineering business, Dorman Long and Co. In 1935, after suffering during the Depression years, the Hoskins family merged its steel operations with Broken Hill Proprietary Co. (BHP) and Australian Iron and Steel and Southern Portland Cement became subsidiaries of BHP.

In 1945, brothers Ken and Don Hoskins entered into a partnership with an initial investment of 15,000 pounds on a small leased area within Southern Portland Cement's works at Berrima. They undertook a contract with the company to manufacture agricultural limestone, with provision for spreading the product on farms. Under the agreement this enterprise's marketing and development was to satisfy the cement company at all times. By meeting these contractual requirements, the new company was assured a considerable degree of assistance from Southern Portland Cement. And in the postwar years, many essential services were provided by the parent company so that a close and cooperative association developed.

Using a simple homemade crusher with bin and bagging facilities, Southern Limestone was capable of despatching 100 tons of limestone a day. The company built a lime spreader that delivered to local farms and the company soon had a fleet of fifteen of these units which operated throughout New South Wales.

By 1949 output had increased to 20,000 tons and the company was incorporated as Southern Limestone Pty Ltd. Important new markets developed in 1950. Firstly, road making used an increasing volume of limestone filler; secondly, CSR began producing floor tiles, which required a special grade of limestone; and thirdly a modest start was made to supply higher-grade limestone - which the plant could now process - to the glass industry.

Despite these developments in the early 1950s, expansion was severely hampered by postwar shortages. Electricity, rail trucks and paper bags were all in short supply; even telephone calls to Sydney were rarely connected in less than an hour. At the time, electricity was perhaps the most critical factor for Southern Limestone. The County Council electricity supply was unreliable and costly. Southern Portland Cement's powerhouse was fully stretched in meeting the combined needs of the Berrima cement works, the Marulan quarry (which was connected by a private railway line) and the modest needs of Southern Limestone.

Due to these restrictions, Southern Limestone was quoting six to nine months' delivery for its limestone. This situation soon encouraged other producers to appear in country areas, particularly the north coast of New South Wales where there was increasing demand for the product.

Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers was originally incorporated as a proprietary company in 1960. In 1964 it had been converted into a public company in order to acquire the Australian interests of the UK-based Blue Circle Group of companies.

In January 1974 BHP, who owned Southern Portland Cement, and Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers agreed to merge their interests. This entity became Blue Circle Southern Cement.

The Second Changing of the Guard

| Boral in 1986 | |

|---|---|

| Total Sales Revenue | $1,969,373,000 |

| Net Profit before tax and depreciation | $346,382,000 |

| Net Profit after tax and depreciation | $165,185,000 |

| Assets | $1,657,699,000 |

| Number of Shareholders | $51,612 |

| Dividends paid | $71,766,000 |

Eric Neal retired as Boral's chief executive in June 1987 after thirty-seven years' service and fourteen years as chief executive and managing director. He remained on the board until April 1992. In the year Neal retired the operating profit was $178.1 million, compared with $12.6 million in 1973, a rise of 141.3 per cent - an unbroken sequence of higher profits.

Tony Berg, Boral's managing director in 1996 commented, 'Neal was a great leader of Boral. Looking over the fifty-year history Boral's position today can largely be credited to Neal and what he achieved during his fourteen years as managing director. He made acquisitions which were fundamental to Boral's present position and strength in the building materials market in Australia. His management style was also a crucial factor - he left the company lean and aggressive with a no-nonsense approach to the business - which held Boral in very good stead for the future.'

Bruce Kean was appointed to succeed him as chief executive and joined the board. Kean had joined Norman J. Hurll a few months after Boral acquired a 50 per cent interest in 1968. A chemical engineer by training, he started off as marketing manager for gas and oil-fired burners and mechanical business. Kean followed the classic Neal scenario - he worked his way through the company and took over the management of Boral's Brick Group. Kean then succeeded Neal as chief general manager, Boral Gas Group, when Neal became chief executive of Boral Limited. There was no sector of Boral that Kean had not actively managed except resources - concrete and quarries - and in 1987 he was invited to become managing director.

Kean had a strong philosophy inherited from Neal that a general manager was exactly that - a manager of the business generally. His view was that the job involved hiring and firing, accounting, maintenance, recommending new capital equipment, marketing, cash flows, meeting customers and collecting debts. Boral's general managers were totally responsible for every aspect of their business.

Kean recognised that a lot of Boral's financial control systems could be traced back to the company's original business of marketing bitumen. Kean comments, 'In those early days, Boral was making a product which was produced out of a high capital cost plant that couldn't be stopped. Refined products couldn't be stored for an extended period of time.' Boral's business was built on cash flows, aggressive marketing of its products and a central control system.

When Neal took over from Griffin, Boral was still buying up companies to soak up the by-products of the refinery. For example, when Boral went into the gas industry, management was looking for a way to capture the market for LPG and naphtha gas that came off the Matraville refinery. Boral also got into road making to use the bitumen, and the company bought into bricks to utilise the refinery's heavy distillates. Kean said, 'Businesses were acquired to provide a market for the by-products of the refinery. This was vertical integration in its classic phase.' When Griffin decided to sell the refinery, he was left with all these varied businesses. Kean says of this event, 'All the subsidiaries were suddenly left without a "father" or "mother" - they were orphans unrelated to each other.'

The challenge for Neal and the Boral board was to form a matrix that made these businesses viable. Kean said, 'From the quarry, fine aggregates went into roof tiles, medium aggregates went into concrete blocks and coarse aggregates went into road making. Quarry products were all tied together with bitumen. Concrete took Boral into reinforcing steel. Bricks matched up with roof tiles and these products, together with masonry and aluminium windows and doors meant the company was now supplying the full external cladding for houses. Boral then went into gypsum board -- internal linings -- building up a family of integrated products, defining their markets as house building, construction and the associated infrastructure.' By the time Kean took over from Neal, Boral's role had been totally redefined to incorporate building and construction materials supply, building services, building maintenance, gas and other manufacturing.

In September 1987, Boral announced a new issue of approximately 55.4 million ordinary shares to existing shareholders on the basis of one share for every ten shares or notes held. The issue was intended to raise approximately $277 million to finance a number of expansions, both in Australia and overseas, relating to the Group's core businesses. This issue had not closed, however, before the share market crash in October 1987, and overnight the price became unattractive to shareholders. At the Annual General Meeting on 9 November 1987 Peter Finley, Boral's chairman, announced that the issue would have to be abandoned and shareholders who had applied for shares were free to request a refund.

Bell Basic Industries

On taking charge, Kean knew that Boral did not have strong representation in Western Australia. In 1987 Boral had purchased Calsil's masonry operations Australia-wide. This company, based in Western Australia, was the market leader in that state. A further opportunity came along when Bond Corporation bought Bell Resources from Holmes a Court and promptly set out to sell off the quarrying, concrete, asphalt and transport operations as Bell Basic Industries. Boral eventually bought the company, a move that took them into Western Australia in the resource and transport industries on a large scale. Kean recalls having some hair-raising discussions with Bond Corporation executives while negotiations were in progress. He said, 'Deals were made on the end of the telephone, with no documentation whatsoever.'

Midland Brick Acquisition

Midland Brick in Western Australia provided the next opportunity. Ric New, managing director of the company, was a friend of Bruce Kean. In the late 1970s, Boral made a bid for Brisbane and Wunderlich's (now Bristile) brickworks in Western Australia, but that attempt had failed miserably. Neal had planned a market raid but the chairman of Brisbane and Wunderlich's board at the time was also chairman of the West Australian Stock Exchange. The Western Australian business community, which did not take kindly to Boral coming in and trying to buy up a local business, rallied round and staved off the bid.

Neal didn't want to be seen to be giving up in Perth and Kean, being general manager of the Boral Brick Group, was assigned to show that Boral was still interested in the local brick industry. He went on a tour of the hills around Perth drilling for clay, and applied to a number of local councils for permits to build a brickworks. He made very visible overtures, but what he did not realise was that Bond Corporation was following him. Bond owned Whiteman's brickworks and Boral had already made three attempts to buy it without success. Bond kept overbidding Boral on the clay deposits. This didn't worry Kean in the slightest; Boral never had any intention of building a brickworks.

Ric New, who owned Midland Brick, also got wind of this activity and arranged a meeting with Kean to discuss Boral's interest in Western Australia's brick industry. He told Kean that Boral's actions were the height of stupidity. Western Australia was already oversupplied and New said that Midland Brick could build a brickworks quicker and cheaper, annihilating any outsider who tried to enter the market. New conceded, however, that he was a one-man band and that at some stage he would have to sell the business. If Boral really wanted to get into bricks in the west, he advised that the best thing it could do was be patient. He was quite prepared to shake hands in a gentleman's agreement with Kean, to ensure that Boral would have the first right of refusal when he did want to sell. However, there was neither a price nor a time set on this deal.